Loser mode

Pulling out a giant whiteboard for U.S. climate policy.

Before I get to the main content of this newsletter, I should say this first:

No kings—and no colonies!

This past week, Trump took control of the DC police department and brought National Guard members into the city. ICE and DHS agents were already active the city, arresting people in our park spaces (run but rarely maintained by the National Park Service), and now they can operate across the city with even greater impunity. There are more cop cars, there are more helicopters, and there are a lot more disruptions. Federal agents are already blocking streets, pulling over cars, and making arrests. They are tearing down encampments without notice, too. Many of them wear masks and don’t provide agency identification. Lots more of them just loiter around—more than the normal amount. Our mayor is more or less cooperating with all this.

Both to better protect the rights of my neighbors and for the future of the progressive politics in this country, DC needs statehood. No kings—and no colonies.

My community’s support networks need help for the tumultuous weeks ahead. Here’s what I can suggest:

Support Free DC, the key organizer network supporting the city’s defense and push for statehood. Donate and sign up to organize with them.

Donate to Ward 1 Mutual Aid and Ward 2 Mutual Aid. These are both wards I’ve lived in. Money goes toward supporting homeless neighbors living in encampments, supporting displaced tenants, and providing groceries and community services.

Donate to Aparna Raj’s campaign for DC Council—she’s an organizer here in Ward 1 who will fight for DC statehood and against Trump, as well as for a lot of other important causes such as affordable and social housing, tenant protections, and school funding.

Free DC!

Loser mode

For the past three years, my friends and I have played in a recreational softball league.1 We’re pretty good, objectively, but we lose about as often as we win. Sometimes it’s because our opponents are just bigger people, with harder swings. But sometimes it’s because we bat straight toward their fielders, or because we let fly balls slip behind us when we’re on the field ourselves. My friends are much better at diagnosing exactly what goes right and what goes wrong during our games—some of them have played for years and have an almost preternatural sense for judging our performance—but what’s important here is that I’ve never seen them try to argue that we played better than we did. There’s no sugarcoating a loss; the only thing to do is to get really precise about why things went the way they did, and to plan for the next game accordingly. We take this pretty seriously, if a little farcically so: Our post-game debriefs involve drawing sloppy softball diamonds on an extremely large whiteboard, retelling specific plays, and pointing and exclaiming a lot.

If you’re a loser—and I have often been, at sports in particular—then I think you should figure out why you lost. And if you’re slated to play again next week and if you care about winning, you should figure out how to do better. But the latter requires a really good understanding of the former.

Now, with that out of the way—this post is about climate policy. Today, celebrating the third anniversary of the Inflation Reduction Act, I’ve got a new long-read up in Heatmap News: “Now We Decide the Future of Climate Policy.”

I do not claim to figure out why Democrats lost the 2024 election, nor why Republicans repealed the IRA so summarily; I have my thoughts, and many people, me included, have already spilled some ink on the subject. But Democrats have no choice but to play the climate policy game next week, the week after next, and for the foreseeable future—and, if they care about winning, they should figure out how to play better.

This is my attempt to pull out a giant whiteboard, draw some softball diamonds, and gesture excitedly about our batting and fielding:

IRA and BIL were paradigm-shifting attempts at market-shaping. … IRA and BIL were not, however, a comprehensive climate policy. …

Taken together, BIL and IRA expanded the energy tax credit system, created powerful programs for piloting and deploying innovative energy technologies, and seeded an ecosystem of regional financing institutions devoted to more equitably distributing the benefits of decarbonization. But the energy tax credits were never expansive enough; the programs intended to motivate investments into deeper decarbonization were not flexible enough to drive the mass uptake of emerging technologies; and efforts to decarbonize disadvantaged communities lacked a coherent strategy and ran headlong into local capacity constraints.

Speeding up the energy transition and building new infrastructure at scale requires endowing federal and state agencies with adequate appropriations, access to liquidity, and crystal-clear, wide-ranging mandates, as well as empowering them in statute with considerable flexibility as to the financial products and strategies they deploy to achieve those mandates.

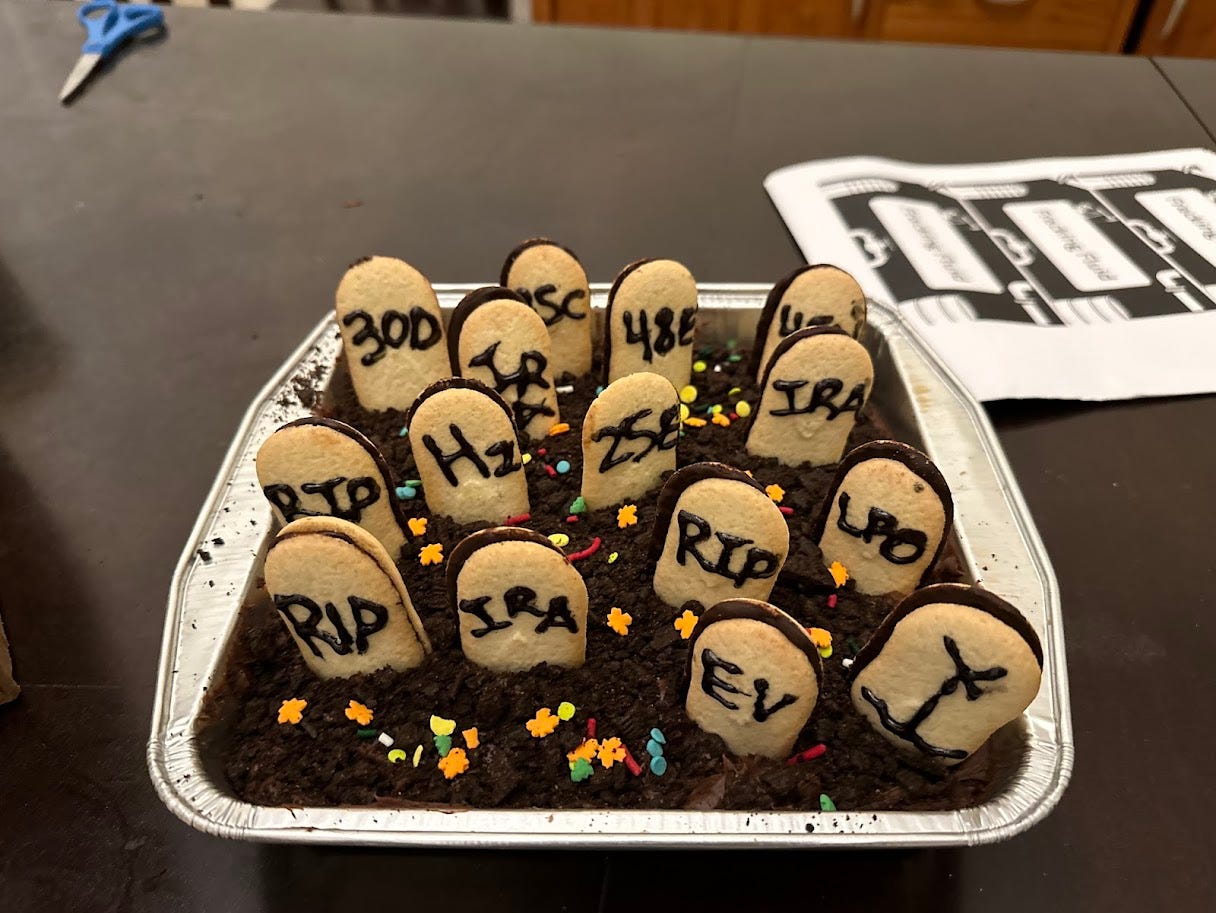

I argue that, for all BIL and IRA’s promise, and for all the investment they did mobilize, the “bottomless mimosa” of tax credits were not expansive enough, the LPO was not flexible enough as an engine of deeper decarbonization, and that the GGRF was horribly designed. I want to explain the precise structural reasons why these advances never went far enough. (This is my attempt to straddle the line between “team transformative” and “team inadequate” with respect to last summer’s IRA-focused derisking debate.)

I also took some shots at how national security politics have just completely eaten up our energy policy conversation—perhaps the price of passing the IRA, but the Achilles heel of Bidenomics itself. I don’t think it would be bad for Democrats to stop playing the energy policy game on Republicans’ terms:

Here [in New Orleans], climate policy is not about combating Chinese supply chain dominance, or even about delivering an American industrial renaissance. It’s about keeping the lights on, keeping bills low, keeping the air clean, and keeping residents safe from disaster. … cost-of-living-focused voters could be far more vocal, relevant, and hungry for change than a coalition built on vague sabre-rattling against China.

The piece isn’t short, but it’s my best attempt at a full accounting of everything I’ve observed about the process of IRA implementation itself. Please read! And let me know if you need a PDF.

Unsurprisingly, and very reasonably, a lot of content got cut. Here are a few fun bits. I make no promises as to their quality, which was, sometimes, why they were cut:

“Democrats will have to build these pillars back better.”

“The energy future promised by the Trump administration is not bright — in fact, it’s already flickering.”

“The communities most in need of federal support, however, are often the least able to secure it. Economic development in the United States, particularly in poorer communities, often rests on the backs of overworked, understaffed local governments and nonprofit community organizations struggling to secure some mix of public grants and private investment in one-off projects. Few of them are investment professionals or energy modelers, nor do they have time to be. Yet they are the ones responsible for applying for competitive grants ― which, if awarded, often come with onerous reporting requirements, to say nothing of the challenge of pooling grants together ― and wrapping their heads around how to raise debt and how to secure a direct payment of tax credits from the IRS.”

“At the conservative-leaning Energy Imperatives summit in June, in Washington, D.C., speaker after speaker emphasized the need for grid reliability to meet the tech sector’s seemingly insatiable energy demand. Yet I can’t recall a single one mentioning the New Orleans power outage. In the meantime, many venture capital-backed energy ventures ― seeing the obvious demand pathways available to them ― are rapidly shifting their messaging and their investments toward servicing tech companies and the defense sector rather than the grid or clean energy. The political economy trend here is obvious: Reliability for Meta, and blackouts for NoLa.”

Anyway, happy third birthday to the IRA. :)

Cool things I’ve read/watched lately:

I saw a performance of King John at DC’s Shakespeare Theater Company. I had never read or seen this play before—and most Shakespeare fans I know haven’t, either. I honestly have no idea when I would next have the chance to see this show, so I went, and I quite enjoyed it. The performance really successfully worked the script into something more than just a fast-paced war story: The Bastard Faulconbridge, Prince Arthur, and the aide Hubert all tugged the idea of loyalty into a more capacious and generous shape, and King John’s descent into fever seemed like a physical manifestation of the chains that making, rather than breaking, promises imposes on him. I also loved the Bastard Faulconbridge’s monologue about “That smooth-faced gentleman, tickling Commodity,” and its ability to break even the covenant between King and Church. If there’s one thing that took me out of it, it was the pop music and dance interludes. I won’t explain that.

I watched Eddington and I have this to say: I really really liked it, but I don’t want to see it again for the next five years. Way too much secondhand embarrassment about our collective COVID-19 neuroses. Props to the movie for accuracy. Where the movie’s plot is concerned, the way Eddington depicts the growing use of screens for processing and communicating information, the quite literally arms-length nature of seeing the world around oneself, has haunted me since I’ve seen the movie. It’s a movie about fear landscapes mediated at first through the internet that then come to dominate reality itself; Joaquin Phoenix’s Sheriff is an extremely dark character, but his darkness feels almost sad to me given how much control he loses over the course of the movie. The movie takes quite the absurd turn, but I think it’s justified given the feelings it put in me. (It’s telling that, by the end of the movie, we still haven’t learned if the Sheriff got COVID. In Eddington’s universe, COVID really might not be real!)

I read Hilary Mantel’s Place of Greater Safety. I loved it. I will probably have more to say about it at some point, for just how thoughtfully it approaches the contradictions of power, obsession, and holding to one’s principles—and how it approaches the heart of friendship itself. How Mantel frames the life and times of the Jacobin trio, Robespierre and Desmoulins and Danton, is a masterpiece of characterization. Can you believe she wrote the first draft of that book when she was twenty two?! Some fun lines:

“Factions rise and fall. The tradition of loyalty endures.”

“No one ever knows what anyone else is saying ... [in] our rooms that were designed for something else.”

“We may be tainted with pragmatism, but it only needs a clash of personalities to remind us of our principles.”

“You can't stand in the street calling into question the last five years of your life, just because they've changed the street name; you can't let it alter the future.”

CW’s “age of enlightenment” reviews Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, taking a refreshingly existentialist look at the confused ethics and subjectivity around the idea of adulthood:

that is not to say that edna should be free of the consequences of her own actions, but rather that the deck is stacked against her from the start: even if she develops the will, she never develops the ability to actually contribute to the world that she lives in.

to return to contemporary politics, then: much of right-wing political discourse frames childhood negatively: a child has to be protected, regulated, restricted against sin, danger, and their own bad decisions. maybe it is important for the left to conceive of the experience of childhood positively: as one of growth, in which case it is crucial that we give all children the freedom to explore and complete that process without prefiguring the outcomes.

We play so kids play free.