The belligerent idealism of climate realism

Don’t call it “bipartisan” or “pragmatic”; it’s anything but.

To work on anything, liberal or conservative, during the Trump era is to run the risk that it will immediately be overshadowed by events outside of your control. This political chaos has become the occupational hazard of policy work today; every idea―no matter how conservative or bipartisan―now stares down the barrel of its own irrelevance. This state of affairs may have gone sour, but there’s sugar in this lemonade yet: Freed from needing to judge policy proposals solely on their political prospects, we can and should consider them on their substantive merits, too.

Take the Council on Foreign Relations’ new Climate Realism Initiative, which launched on Monday, April 7 as a bold backward leap toward “bipartisan,” “pragmatic” climate policy―and slipped immediately into media irrelevance1 when stock markets collapsed against President Trump’s then-refusal to back down on his tariff threats.

In retrospect, for the best: The Climate Realism Initiative smuggles bad ideas within predictable policy pablum about the virtue of fiscal responsibility. It’s unimaginative at best and dangerous at worst.

In his inaugural essay, the director of the Climate Realism Initiative, CFR Senior Fellow Varun Sivaram2, presents the provocative tenets of “climate realism” as a series of hard truths: We’re going to overshoot two degrees Celsius, U.S. emissions reductions effectively don’t matter, climate risk is a catastrophic threat,3 and the clean energy transition will not be a win-win situation.4 Rather than advocate for international cooperation toward rapid emissions reductions—a strategy which apparently amounts to “magical thinking”—Sivaram thinks the U.S. should proactively invest in domestic disaster mitigation and prepare for internal climate migration; leapfrog Chinese technology with more innovative, new U.S.-made cleantech; aggressively deter other countries from increasing their emissions through tariffs and trade barriers; and invest in geoengineering techniques like solar radiation management.

Like I said, I think a lot of this essay’s climate politics are dangerous and bad. As Catherine Fraser put it last week in Common Dreams, “it’s hard to imagine a world in which the U.S. could possibly be seen to lead on climate while ignoring its own emissions reductions and sacrificing broad swaths of the Global South to sea-level rise, deadly heatwaves, and cascading crises driven by climate.”

But Sivaram imagines it anyway, wholeheartedly eschewing the “emissions don’t care about borders” internationalism of the 2010s to insist that foreign carbon emissions are different from U.S. emissions.5 He crystallizes this belief in a belligerent argument that “the effects [of a climate disaster] resemble those if China or Indonesia were to launch missiles at the United States,” which he draws from a January brief on U.S. climate risks:

A provocative way to think about climate’s impacts on the United States is to conceptualize these astronomical damages as missiles launched by foreign countries against the United States. It is reasonable to consider the next hurricane with higher intensity attributable to climate change as a missile launched by China’s or India’s continued burning of coal that wipes out tens of billions of dollars of U.S. infrastructure and causes loss of American life.6

In Sivaram’s theory of international relations, climate realism calls for militarized adaptation, even as he admits that “this approach is fundamentally unfair” to other countries. It also necessitates that the U.S. retain global economic hegeomony defined by technological prowess and market share by deploying more innovative U.S.-pioneered technologies across emerging markets and breaking Chinese dominance over the global market for clean technologies.

If that’s his goal, the essay relies on a baffling understanding of American political economy. In the hope that Republicans will support this climate strategy so long as it’s fiscally prudent, Sivaram traffics in what I can only describe as zombie neoliberalism: He calls the Inflation Reduction Act too expensive and badly targeted, and argues that the U.S. needs to balance its budget to leave future generations with fiscal headroom.7 Most bizarrely, he dismisses local economic development as a worthy industrial policy objective; his chief goal for industrial policy is to build competitive export sectors in innovative products.8

Worst of all, this thinking cedes the extremely defensible rhetoric9 behind the Biden Administration’s embrace of public investment to target national objectives. His essay and a follow-up podcast appearance cast a lot of unwarranted aspersions on some of the core tenets of Bidenomics: namely, that government spending can be a market-shaping investment rather than a market-distorting cost, and that driving domestic economic development is inherently important for both political and economic reasons—all this from a former Biden administration diplomat, no less.10 Thus he preemptively surrenders the chance to achieve the very kind of innovation-forward industrial policy he’s trying to promote.11 While there are clear, if debatable, political justifications for gestures toward bipartisanship12, they don’t really explain Sivaram’s total retreat from fortifiable policy positions nor his complete embrace of hawkishness. What gives?

Nearly every policy paper Sivaram has written in the last decade focuses on how the U.S. can leverage its resources to support the development of innovative and path-breaking clean energy technologies to drive down emissions and deliver climate adaptation.

For what it’s worth, this is a productive area of inquiry, and it’s broadly compatible with the goals of liberals and progressives across the 2010s. Sivaram has consistently suggested to policymakers that we support “leapfrog” technologies over what’s already commercialized:

the widening investment gap between deployment and innovation endangers prospects for improving the performance and reducing the cost of clean energy. And by overemphasizing deployment, policy makers can tilt the playing field against emerging technologies, which are at a disadvantage to begin with.

This emphasis on “creative destruction” will show up again and again in his writing: Reject incumbency; it breeds stagnation—it’s very Silicon Valley of him, but it’s not wrong per se. For example, it’s undoubtedly easier for established firms with technologies that most investors are comfortable with to access tax credits and outmaneuver smaller firms and startups.

Still, arguing that policymakers “overemphasize” the deployment of commercialized clean energy technologies (he wrote this in 2017!) looks silly in hindsight. With respect to emissions reduction goals, both innovative technologies and established ones suffer from an underemphasis on commercialization and deployment, even today.

This focus on innovative technologies manifests in interesting ways. For example, Sivaram has been a shooter against photovoltaic solar (or solar PV) for nearly a decade. How he discussed its limits, again back in 2017, is fascinating:

Still, given the rapid growth of the solar market and the continued cost reductions of silicon solar, it might appear that no alternative to silicon is really necessary to meet global decarbonization goals. Such optimism is misplaced. … Indeed, for solar to provide 30% of global electricity production by 2050, Shayle Kann and I have estimated in Nature Energy that solar will have to cost less than $0.25 per watt, which is over four times lower than current costs. Extrapolating historical learning effects, that figure is simply out of range for silicon solar. And if silicon solar hits a penetration ceiling decades from now and a clear investment case emerges for a superior technology, it may be too late to keep global decarbonization on track.

So much for his prediction: The price of Chinese solar is now as low as 11 cents per watt. Sivaram has consistently touted perovskites as the better alternative—and to what end? I don’t fault him for being pessimistic, but I do think it’s striking how his solution wasn’t to drive what’s called “process innovation” (analogous to “economies of scale”) in solar PV technology, but rather to bet on the emergence of a superior technology.

This is a venture capitalist’s understanding of how to change the world. How did he suggest we improve the innovation policy ecosystem to drive the development of these superior technologies? In 2019, he co-authored a paper with Noah Kaufman, at the Columbia Center for Global Energy Policy, about reforming the clean energy tax credit landscape, where Sivaram sees tax credits for solar PV and wind as passé:

Both the solar and wind manufacturing industries are now multibillion-dollar global industries that will continue to increase in scale irrespective of the ITC or PTC. … If the tax credits are no longer leading to meaningful improvements in the cost or performance of wind and solar energy technologies, they are not making future decarbonization efforts cheaper and easier.

The lesson is that tax incentives give the “biggest bang for buck” when they support initial commercial scale-up. It therefore makes sense to allow the current tax credits for solar and wind energy to expire. They will leave behind important lessons for how to design the next generation of incentives13 to be maximally cost-effective in fostering a diverse range of commercially viable clean energy technology options.

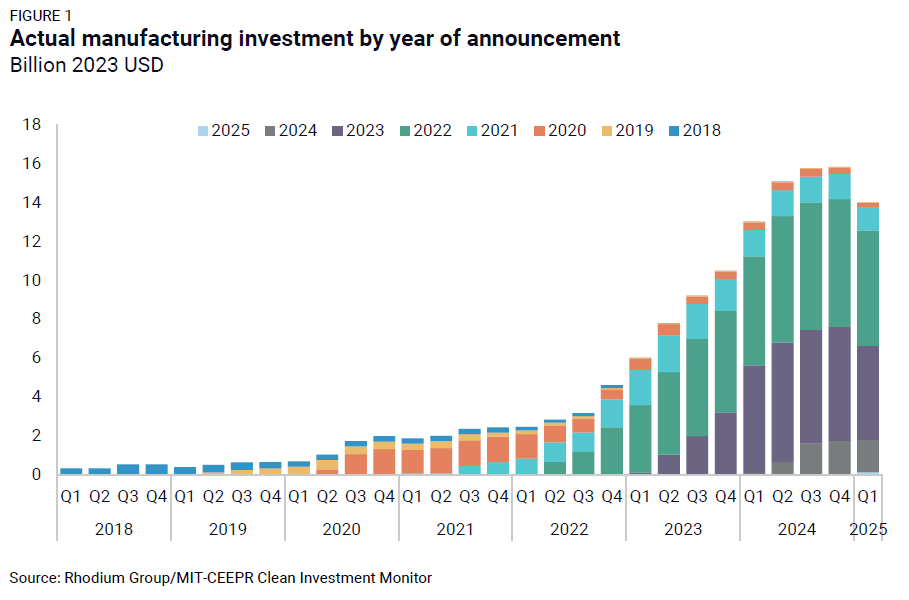

It baffles me that he’s saying, in 2019, that we should have let the tax credits expire, and that they don’t make decarbonization easier. Of course, the U.S. still lacks China’s production or installation capabilities, but, since his assessment, solar deployment has boomed, certainly thanks to tax credit extensions and Biden’s climate laws.14 In particular, the Inflation Reduction Act’s clean technology manufacturing tax credit drove record growth in fixed capital investments. Would he still argue that these tax credits wouldn’t make decarbonization easier—now that the evidence proves him wrong?

At any rate, in their paper, Sivaram and Kaufman endeavor to design a better, more “cost-effective” tax credit that’s technology-neutral and phases out at some threshold for adequate market penetration, even though tax credits are—and I cannot stress this enough—not a useful financial technology for encouraging and scaling up innovative technologies in particular. In trying to game out a technology-agnostic redesign of our energy tax credits, Sivaram and Kaufman are ironically relying on the “incumbent” U.S. economic policy rather than embracing more innovative alternatives that complement tax credits.

That being said, their broader worry that incumbents will lock out new entrants does reveal a working and mostly consistent (if exclusive) definition of “innovation”:

the market may prematurely converge on one technology option that achieves an early commercial lead and then harnesses tax incentives to reduce its costs through economies of scale and learning by doing. This dominant technology option might actually be an inferior technology to other potential options that, despite their higher initial costs, might have steeper learning curves or superior performance.

In Sivaram’s judgment, innovation means developing a technology that has lower projected potential costs and higher per-unit performance/efficiency ratings than the incumbent technologies providing the same service. That means supporting perovskites, which are more efficient than conventional solar cells, and solid state batteries, which can apparently charge an EV’s battery to 80 percent in 15 minutes, in contrast to conventional lithium-ion-phosphate batteries.

Notably, this definition of innovation therefore does not involve explicitly reducing the production and deployment costs of existing technologies like solar cells and lithium batteries by driving economies of scale and learning by doing—which are the boring things that a firm with a “commercial lead” apparently does with tax credits to entrench its dominance. Scaling up deployment and driving “process innovation” are not inherently good outcomes for any technology to achieve if more efficient potential competitors lose out in the process. Never mind that BYD now claims it can charge an EV in five minutes with a standard lithium iron phosphate battery, or that perovskites remain nascent despite a decade of hype.

Years ago, Sivaram essentially decided that technological path dependency per se was a bad idea, and that policy of any kind that encourages it would be an expensive market distortion against innovators and entrepreneurs.

This is the best case I can make for why he might honestly believe today that the Inflation Reduction Act, particularly its tax credit expansions, was “lavish” and “poorly targeted”—despite the funding it did provide toward piloting new technologies. For what it’s worth, I agree with him that it wasn’t enough! And he’s smart to point out that the Biden administration’s grants focused more on building an industrial base for already-commercialized technologies like lithium-ion batteries than on supporting newer battery technologies. (Would you believe: He made this exact same criticism about solar cells and perovskites during the Obama administration, too.) But rather than use his climate realism piece to advance even one suggestion for improving the financing landscape, or to defend current innovation policy in light of serious Republican threats, he criticizes the IRA and calls for a balanced budget—in marked contrast with arguments he’s recently made elsewhere about the need to expand on Biden’s climate and infrastructure laws, defend the Department of Energy, and utilize public procurement.

Does Sivaram want the state to spend on achieving his policy goals or not? Maybe he’s repackaged his views for a bipartisan audience; maybe he’s being purposely two-faced. Either way, the monkey’s paw has curled: The latest budget reconciliation markups from the House of Representatives phase out the incumbent-supporting tax credits and shut down insufficiently innovation-focused grant programs he’s got such big problems with—and they also tear up every other program that might spark the innovation he so badly wants to unleash. Here lies another victim of the bipartisanship racket: passed over by the left and the right, quietly rotting on the Capitol floor.

Tactics notwithstanding, one thing Sivaram’s been consistent about in the interest of bipartisanship is the threat that China poses to the U.S. Of course, there’s the broader national security threat of growing Chinese military power; then, there’s the economic threat that China controls crucial global supply chains and dominates trade with Global South countries; and, finally, there’s the “production frontier threat” that Chinese dominance in commercialized clean energy technologies will snuff out U.S. competition and choke off new technological pathways.

Here, Sivaram is in good company: For better or for worse, policymakers on both sides of the aisle, as well as much of the DC think tank ecosystem, agree with all three of these arguments. But that last threat uniquely fits how Sivaram has been framing the challenge of innovation policy for a decade now. His argument that incumbent firms use their market share, access to policy supports, and economies of scale to snuff out innovative new entrants parlays quite smoothly into his argument that China’s mass production of most clean energy technologies hurts the American innovator. In a piece from 2016, he explicitly stakes the hawkish position that “the United States is losing this race because Asian countries are out-investing it and dictating the terms of competition, often flooding the market with low-cost, unimaginative products.”

That’s still where our Sino-American politics are today. In a sense, anti-China rhetoric provides Sivaram with a discursive “export market” for his long-standing policy program to defeat path dependency. Is Sivaram using the anti-China wave instrumentally, merely as a means to his chosen end of advancing only the very best technologies?

I don’t know. But his use of the word “unimaginative” bothers me. First of all, it’s not true: Chinese process innovations in EV and chip manufacturing15 (the kind of innovation that Sivaram does not treat as innovation) are nothing short of breathtaking. Maybe he couldn’t have predicted this in 2016; few did. But using the word “unimaginative” exemplifies what Andrew Liu, in a brilliant critique of how Western policymakers’ project of their cultural anxieties onto China, identifies as “techno-Orientalism”: At once, the ever-present danger of Chinese market dominance requires a commensurate, “all hands on deck” response—yet this monstrous threat is of course a crude one that can’t dent the egos of smarter and more “imaginative” American innovators.16

The hypocrisy built into this kind of techno-Orientalism is symptomatic of the hawkish strain in American foreign policy. Sivaram leans straight into it.

Bidenomics, to the degree that we can treat it as a coherent policy program, supplied the mulch in which this kind of thinking flourished: Its embrace of state-supported investment in the interest of critical public objectives brought national security hawks, Silicon Valley17, and unionized manufacturing-sector labor into a loose coalition with supporters of local and regional economic development and national decarbonization. For all their limits, the combination of BIL, IRA, and CHIPS really did begin an American manufacturing revival. We had the makings of what could become a real process innovation culture.

Trump’s victory, however, vacated the policy core of Bidenomics, the notion that regional redevelopment and decarbonization are critical national objectives.18 Around its absence flutter the residuals: (1) the continued predominance of national security hawks—anti-China sentiment still runs high in both parties—, (2) the vague gestures toward labor—Trump’s invitation of the UAW and Teamsters to his tariff announcement—, and (3) Silicon Valley—the tech giants, AI developers, venture capitalists, and startups reshaping the economy around AI and its energy demands.

By embracing anti-China hawkishness, tariffs, and the Silicon Valley startup landscape while rejecting government spending on local development or domestic decarbonization, the Climate Realism Initiative is the apotheosis of this “vacated Bidenomics.” And it sucks. It’s hollow and indefensible from a progressive point of view, and it’s outdated and irrelevant from a conservative point of view: Republicans do not give a damn about the deficit and are letting Trump take a sledgehammer to the government and to U.S. hegemony.

Without Bidenomics, the Climate Realism Initiative is ideologically homeless—no one will implement this agenda.

If there’s any chance the policy core of Bidenomics comes back into fashion—a boy can dream—policymakers will undoubtedly ask, once again, how the U.S. can leverage its resources to drive down emissions and deliver climate adaptation. Looking past the current chaos, any satisfactory answer to that question requires jettisoning Sivaram’s incomplete definition of innovation.

The story of China’s technological upgrading proves that innovative market design can spur the development and deployment of both new technologies and innovations on older ones at scale by supporting a culture of startups19 and by driving process innovation. As Jeremy Wallace quipped this week in his own critique of the Climate Realism Initiative, “while supporting next-generation technologies is an appropriate piece of the policy puzzle, they should be like the broccoli at a steakhouse: off to the side and mostly superfluous compared with the meat and potatoes of deployment and mitigation to decarbonize today.” Supporting process innovation through policymaking is just a good idea, one which doesn’t deserve Sivaram’s dismissal.

Last month, Wallace and Jonas Nahm described concisely how competition policy juiced Chinese process innovation:

Chinese firms are winning the race right now because they have made big bets, buoyed by supportive policies. Chinese firms have entered markets, scaled up production, shaved down costs, developed novel technologies, and upgraded manufacturing systems to become world-beaters across a range of sectors critical to the energy transition. Chinese local and central governments aided these firms, but it was running through a gauntlet of cutthroat domestic competition that culled the field and hardened these winners to become the green industries of the future.

It’s not just competition policy. Kyle Chan sketches out how the interconnected market structure of China’s industrial sector drives process innovation, too: “China’s strength across multiple overlapping industries creates a compounding effect for its industrial policy efforts … if you’re already strong in multiple overlapping industries, then this creates a mutually reinforcing feedback loop that further strengthens your position in all of these connected industries.”

For all their flaws, Biden’s three industrial policy laws were a decisive first step toward a more creative, iterative policy approach that spurred an advanced manufacturing boom.20 These laws would not have passed without national security hawks’ support, so it’s fair that the Biden administration catered to them. But, in hindsight, the discursive pride of place Bidenomics afforded to the hawks on both sides of the aisle might have come at the expense of grounded thinking about other possibilities. Sivaram believes that the world will definitely overshoot its emissions targets and that we should prepare accordingly—but this future is not a given. In fact, the world was on track for much worse overshoots just years ago and, if Sivaram’s predictions about solar PV are any indication, I’d like to believe he’ll be wrong again.

Still, let’s say that he’s not, and that the world really is headed for catastrophic levels of warming. It’s baffling, and quite funny, then, to imagine there’d be a global market for innovative American clean technologies in this militarized wasteland future. In cavorting about the market opportunities of disaster capitalism, “climate realism” vacates its own meaning: It’s overconfident, it’s blinkered—it’s downright utopian!

Look alive: That leaves the mantle of real “climate realism” up for grabs. If progressives get a second chance to enact a real industrial policy this decade, they must clear their heads and disavow this belligerent idealism. Better to embrace the pragmatism inherent in sustained international collaboration toward emissions reductions and climate adaptation: What’s progressive is, not for the first time, what’s practical, too.

That applies to this piece as much as it applies to the Climate Realism Initiative. If the economy starts to collapse while you’re reading this, come back later; I really don’t blame you.

Sivaram was the former CIO at Ørsted, the Danish wind power developer, and a former diplomat on John Kerry’s climate team. He’s got an otherwise stacked CV.

You’d think he’d put this list item—that climate risks are a catastrophic threat—up front. Choosing otherwise is revealing: The hardest truth of Climate Realism is not that climate change is dangerous, but it’s to “own the libs” by telling them that they should preemptively give up on our shared two degrees Celsius target.

The transition is not a “win-win” because it hurts the U.S. oil and gas industry. As Sivaram put it in a podcast appearance a few weeks after the launch: “The United States is also now the world's largest oil and gas producer, and that's central to why I think that a global energy transition when we start as a world to move from oil and gas toward clean energy, it won't necessarily be a good thing for the United States.”

The fact that the Global North has accumulated the largest share of historical emissions is, in his words, “probably morally accurate and largely irrelevant for the conduct of American foreign policy. … I don't think foreign policymakers have within their reasonable array of choices and option to go and rectify historical inequities.”

Under no circumstances should we normalize this kind of thinking. Please don’t!

He framed this argument in bizarre terms during his podcast appearance:

What can we afford to do? In my opinion, and this is a point that I don't think anybody has ever raised except me. The most compelling reason for fiscal prudence, for balancing the budget, for reducing our national debt and deficit is the specter of climate disaster in twenty, thirty, forty, fifty, sixty years. And for America to have the dry powder we need to adapt. If we don't have fiscal space, we won't be able to invest in resilience.

Beyond the fact that this is just wrong, I can’t help but chuckle: Really? Nobody except you has argued for fiscal prudence and for balancing the budget? I can’t believe that someone who worked in international climate finance diplomacy is saying this.

He says as much during his podcast appearance:

the Biden administration did not follow the climate realism doctrine, which is laser focused on what the goal should be with clean energy policy. It's to develop globally competitive American industries. It's not to reduce American emissions in the near term, relatively trivial impact on climate change. It's not to create good well-paying jobs domestically, which is a wonderful thing to have, but often is orthogonal to actually creating globally competitive industries.

I really do think the past five years shifted the overton window toward a broader embrace of the importance of state intervention in the economy. Hope that’s not just me?

I understand that many people, him included, might think that these aspects of Bidenomics didn’t win the 2024 election—but, let’s be clear, they certainly didn’t lose the election.

Some of this must be think-tank brainworms; much of the DC think tank world focused on energy and industrial policy was already shifting noticeably toward the political center in 2024, in the hopes that they could play to Republicans’ apparent interest in issues like permitting reform, grid resilience, and competing with China.

Before inauguration, threading the bipartisan needle seemed plausible. Now? Honestly, I think it depends. It’s a useful kind of pragmatism for policy wonks to stake out how they’d solve problems that politicians care about, to mark their territory on the policy map, as it were, by showcasing their command over all facets of any particular issue. (This is probably why so many think tanks duplicate work. Who doesn’t want to be treated as the expert in something?) If that means getting in front of Republicans to talk about how to finance nuclear energy or something, that’s one thing.

But this Climate Realism Initiative? With the way it embraces its hawkishness?

This piece commits the time-honored sleight-of-hand of saying “bipartisan” but meaning “conservative.”

To this, I’d say: The way politics is going these days, there won’t be a next generation of incentives.

There are real critiques of the U.S. tax credits, to be sure. But folks like Brett Christophers would argue that other more intensive subsidy regimes like feed-in-tariffs and contracts for difference are necessary policies to sustain solar energy deployment, rather than policies that can be withdrawn once the industry reaches apparent maturity.

I highly highly recommend this piece and this piece from Kyle Chan.

I highly recommend reading Liu’s essay on the “Asiatic” form, published in 2022 in reaction to the virulent lab-leak theories circulating in the U.S.:

East Asia is either a hypermodern civilization that reflects the degradation of Euro-America, especially the US — think viral tweets comparing Chinese subways to New York’s MTA — or, conversely, it is an economic threat that will one day overtake Euro-America, subsuming it within itself, completing the circuit of Hegel’s Weltgeist, from East to West then back to East. To much of the world, Meredith Woo has written, the region signifies both miracle and menace.

Indeed, Silicon Valley—as a metonym for tech giants and the venture capital ecosystem around them—was definitely willing to play with Bidenomics given the administration’s interest in AI, data center buildout and energy demand, and on-shoring chip manufacturing. In fact, they helped shape the administration’s focus on these issues!

My best evidence for this claim is the indiscriminate cuts that Trump and Musk are making to the government and all its spending programs, which have ground the implementation of much of Biden’s three industrial policy laws to a halt.

Or at least a culture of heavy investment into research.

Just as Chinese policy encouraged joint ventures between Chinese and Western companies to drive both technological upgrading and process innovation, U.S. policy should encourage the same.

20 footnotes is crazy work tbh

This is a great article. The US tried the leapfrogging strategy with pv thin films when they decided in 2010 that tech was going to be the direction that public policy would support instead of supporting crystalline silicon. For example, through ARRA only “precommercial” innovative, tech technologies were able to apply for loan guarantees. A few years later, Sivaram’s Solar book doubles down on argument, with perovskite thin films.