2015 was a pretty good year for corporate April Fools jokes: Netflix told everyone to go outside, Airbnb advertised listings for neolithic caves, DeviantArt released a battery-free stylus that can draw on any surface,1 and Uber and Tinder jointly launched “Uber for Tinder,” which worked exactly how you’d expect. This last joke parlays neatly into the long-running meme about venture capital that every startup pitch is some stupid Mad Libs play on whatever you can think of. Uber for dogs, Tinder for HR2, Goodreads for running—you get the point.

But the meme didn’t originate in the Uber’s and Tinder’s joke. Years before, in 2009, XKCD beat Uber and Tinder to the punch. Turns out the “Uber for Tinder” trope is itself a trope of a trope.

To be clear, there’s truth to it.3 It makes sense that founders had to pitch their startups this way4, if only because the people they’re pitching to are inclined toward interpreting the world through the technologies, services, and concepts they’re already familiar with. There’s alpha in knowing what your audience wants and delivering it to them on a plate. But the Founder, that archetype of venture capital whose one commandment is “disrupt,” must thread the needle between, on one hand, couching their ideas in familiar idioms and, on the other, selling some novel moonshot that just needs some faith, some Series A equity, to transform the world.

Unsurprisingly, many founders fall far short of their shared mythology. For example, I have a high school classmate getting Y Combinator funding for a startup that amounts to “AI for therapy.” In addition to the fact that this line of work sounds, uh, bad,5 its only innovation is in updating this corporate Mad Libs for the era of artificial intelligence—which, as people seem to be declaring breathlessly these days, promises to be the ultimate disruptor of any sclerotic human system. AI for scheduling, AI for drug discovery, AI for government, you name it: Not only has someone already thought of it, but they’re frantically trying to fund it.

This is the Venture Capital Mad Libs formula: Combine something that disrupts with something that needs disrupting.6 Once you start seeing it, it’s hard to shake.

This Mad Libs trend is all over the energy sector. These past few months at work, I’ve been drilling into the market structure of enhanced geothermal energy,7 which promises to turn underground heat into a stable electricity source. Along the way, I met with some philanthropists and policy wonks who want to replace natural gas in our energy system with geologic hydrogen (naturally occurring underground deposits of hydrogen gas).8 We’ve derived the technologies for accessing both underground heat and hydrogen from how we already extract oil and gas from underground shale formations—that is, through fracking technology.9 The proponents of both enhanced geothermal and geologic hydrogen advertise these energy resources in precisely this manner: If the U.S. has already commercialized fracking to great effect, then, the logic goes, enhanced geothermal and geologic hydrogen would be proven next steps.

Fracking for heat; fracking for electricity; fracking for hydrogen; fracking for—we’re just playing more Mad Libs, aren’t we?

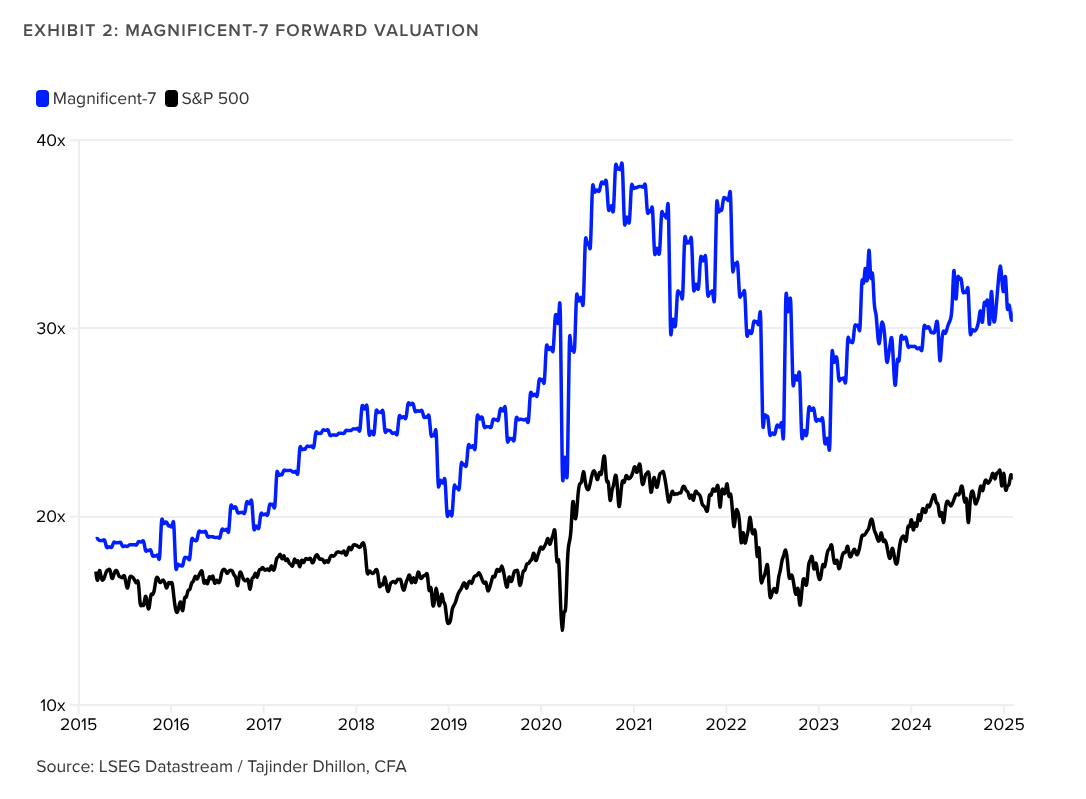

It’s true: Fracking is about as American as apple pie. But these advocates cut corners when they use this relationship to suggest that the success of the former augurs the success of the latter. In a report I published this week, called Committing to the drill bit, I highlighted why this comparison does not work:

Put simply: [enhanced geothermal] is not fracking. … Policymakers and advocates hoping for another great fracking boom, this time with the clean energy of enhanced geothermal, are implicitly assuming that the same economic and financial conditions that drove the shale boom of the late 2000s and early 2010s can be replicated in the enhanced geothermal sector by virtue of its technological profile. But, for the most part, they can’t.

If this comparison is overstated, it’s still worth asking: What about “fracking” is so compelling in the first place? Why does it take pride of place in our game of energy Mad Libs? Well, because fracking is an accredited Disruptor of Industries. If you didn’t already know that the shale fracking boom represented over $300 billion dollars of losses to investors, in aggregate, between 2010 and 2020, well, now you do:

This figure defies belief; fracking went gangbusters.10 Much of my report describes the potential reasons why investors never saw fracking as a threat to their bottom line (until, of course, they did). These unconventional shale drilling technologies kept consumer prices low, silenced persistent worries about energy scarcity, physically transformed the American energy landscape and, I am not exaggerating, turned the U.S. into a petrostate.

Forget whatever software plays I joked about earlier. Fracking? That’s what real disruption looks like.11

What about at the other end of the Venture Capital Mad Libs Formula? Why do sectors like heat, electricity, and hydrogen need to be “disrupted” by fracking so urgently?

The obvious answer: We’re in an energy crisis, and fracking happens to be a tried and tested energy solution. This crisis is material, of course: The United States truly isn’t building enough new energy resources to meet the skyrocketing energy demand from the tech and manufacturing sectors, all while decarbonization requires that we limit our emissions, and under the constraint that most clean energy resources depend significantly on brittle foreign supply chains. Fracking, as adapted for this energy crisis, is an American technology that allows us to extract large quantities of zero-emissions energy sources quickly.

More broadly, however, this crisis is also narrative: Many of the news pieces, reports, and whitepapers hyping up the potential of innovative clean energy technologies—carbon capture, hydrogen, biofuels, geothermal, small modular reactors—are all doing so specifically on the grounds that these technologies achieve some combination of (1) addressing surging AI demand and (2) sidestepping American dependence on Chinese clean technology supply chains, both of which are bipartisan policy priorities. (And, depending on whom you’re asking, maybe (3) mitigating climate change.)12

In short, in the accounts of most policymakers and market actors, the energy sector needs to be disrupted through innovative clean technologies on account of this sector’s material and narrative importance:

Energy startups have overtaken the makers of electric cars and batteries as the top global climate tech investment for the first time since 2020. They’ve done so as the growing demand for artificial intelligence has driven interest in technologies that can power data centers with less emissions.

Venture funding for global energy startups totaled $9.4 billion last year, representing an increase of 12% from 2023 levels, according to a report published Tuesday by Sightline Climate, a market intelligence platform. Among them, funding for geothermal startups nearly tripled to $558 million, while nuclear investment almost doubled to $1.9 billion. … Meanwhile, energy is slated to be a continued hot investment area in 2025 thanks to AI.

(Conveniently, pivoting from “climate” to “national security” in line with the Trump administration’s stated priorities seems to pay dividends.)

By contextualizing and justifying why some sector needs to be disrupted, these narrative hooks connect an accredited Disruptor of Industries to an agreed-upon Sector That Needs Disruption.

But isn’t this just what successful storytelling requires? How else are people supposed to generate hype for something? In a world where many important people fret about AI demand growth and about Chinese dominance of existing clean tech industries, it only makes sense for smart entrepreneurs—founders and policy wonks alike—to offer the kinds of breakthrough, lower-cost/higher-impact solutions the people who pay them might prefer to hear.

Narrative demand calls forth narrative supply. The fewer visible political and economic obstacles, the cheaper it sounds—and, in this economy, disruption sells. It has lower upfront capital costs than the alternative, comprehensive systems thinking driven toward methodically and systematically improving something.13

These specific narratives carry so much weight for a clear material reason: The stock market is overly concentrated around the fortunes of the tech industry, now riding—and, a little bit, creating—the wave of the AI demand boom. The “magnificent seven” tech giants comprised 36 percent of the S&P 500 stock market index at its peak in December. Indeed, the tech sector sets the pace of the U.S.’s broader economic growth trajectory:

Sectors where we see clear AI-related investment demand now credibly compose 7% of the US economy. For context, back in the 1990s tech-telecom boom, we reached about 6% as a share of the economy. These GDP shares have been swelling more meaningfully of late thanks to the torrid growth rate of data center construction. Taken in the aggregate, AI-relevant segments mentioned earlier are growing nominally at a 15% annualized pace, with clear signs of acceleration in recent quarters.

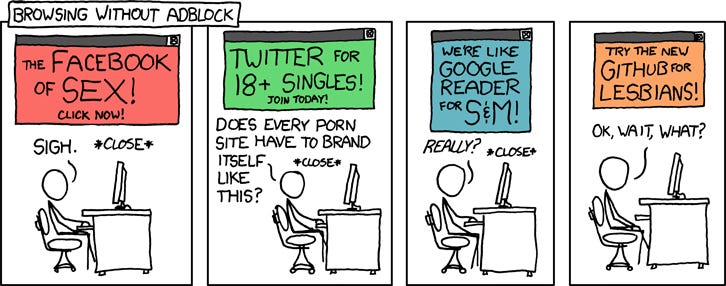

And the price-to-earnings ratio of the “magnificent seven”—the ratio of their stock price to their earnings per share—is far higher than that of the overall S&P 500 index, even accounting for the 2022-23 interest rate hiking cycle.

In layman’s terms, this chart reflects that the tech giants are substantially more valuable investments than all other publicly listed companies, and implies investors’ faith in these companies’ future cash flow generating potential. Stock prices, after all, reflect market actors’ beliefs. It doesn’t mean they’re right or wrong about the AI boom—either way, those beliefs are shaping reality. In a sense, these price-to-earnings ratios are financing the AI boom into existence, rather than the other way around.

Of course, everything’s more volatile now.14 But “the markets,” in their infinite and infinitely blinkered wisdom, still trust the AI growth story—which, despite being a story, a narrative about the direction of the economy, has material knock-on effects for any sector its growth relies on, like energy.

All of which is to say that the returns from investing in the tech giants become the collateral that funds the market’s interest in the sectors and the disruptive technologies that are supposed to support that growth.

So the Venture Capital Mad Libs process can successfully generate arbitrary combinations of familiar ideas—fracking for heat, gravity for energy storage, nuclear batteries for space exploration(?)—that slot compellingly into a prevailing economic narrative hook. Whether or not these narrative hooks are good for society—that’s a debate I won’t get into here. It’s possible that most of these disruptive technologies will turn out to be hot air15; it’s likely that most of what we call “artificial intelligence” is vaporware.

But, in exploring how the broader economy legitimizes these games of Venture Capital Mad Libs, I’m also realizing that venture capitalist clean tech types and I view financial markets from different epistemic vantage points: They work with equity; I work with debt. Paraphrasing Ven at Malt Liquidity, equity provides liquidity to hope, whereas debt provides liquidity to trust.16

I’ll reverse that framing: hope provides liquidity to equity and trust provides liquidity to debt. Structurally, for all the reasons I’ve explained above, there’s a lot of hope providing liquidity, in the form of equity, to these disruptive clean technologies. There’s a cottage industry built around justifying their potential in light of the current narrative landscape.

But the “narrative buy-side analysis” I’m doing here and in my geothermal report should highlight why there isn’t yet that much trust in the hype. There is no comparable cottage industry of investment memos or underwriting criteria from financial institutions or credit rating agencies clarifying how longer-term debt investors ought to work these technologies into their portfolios. This is where the equity-market narrative of disruption runs up against debt markets’ discounted cash flow analysis. Enhanced geothermal energy, for example, may fit into the broader category of “energy infrastructure,” but project finance investors can’t get consistent answers as to how underground resource extraction happens; what the cost breakdowns between heat discovery, flow testing, and power station construction are; what the financing requirements are; or how these projects fit into the broader energy grid to generate consistent revenue. Because project debt investors do not trust the financial and legal landscape surrounding these new technologies, they will deny developers the kind of liquid project finance they need to scale up.17

Of course project debt investors still need to get familiarize themselves with the technologies they’re financing. But, while venture capital investors are making competing bets on which of these technologies are the best—from a cost perspective, from an efficiency perspective, from a productivity perspective—project debt investors fundamentally just want to know that they can trust the tech to work and keep working until their loans have been repaid. Their trust in any given technology depends on their trust in the functioning of the broader market it’s in. In the end, hope only gets you so far.

i.e., a pen.

There’s truth to most, if not all, xkcd comics. I’m particularly fond of “Goodhart’s Law” (I wrote about it!) and “Standards.”

The same way YA authors use tropes to drum up enthusiasm for their books, or (stretching here) the way Spotify creates genre categories for its auto-generated personalized “daylists.”

It does not help that this classmate styles himself as a disruptor, if LinkedIn posts are anything to work off of.

Some entrepreneurs monetized the meme itself as a “Mad Libs for startup ideas” party game called Snake Oil Salesman that you can buy for $25. (It’s very fun, highly recommend.)

“Committing to the drill bit” was my working title, and somehow everyone else agreed it should become the real title. Here’s the summary table, which should give you a sense of my project:

Parts of the report get nerdy. We talk about option value, duration risk, and own-rates of interest. Many thanks to Yakov for helping me flesh out some of that.

I think it’s promising! It also requires major policy support. But that’s true of most good ideas, and I haven’t studied up enough.

And if you’re at all interested in clean energy and climate change mitigation, your next question should be: “How can we set money on fire like this for clean energy?”

I’m updating the hammer/nails quote: “When all you have is a drilling rig… everything looks like something you can frack?”

I do not believe the material crisis and the narrative crisis converge perfectly. The material crisis is biophysical and, to some degree, reflects path dependency in industrial capacity and supply chains. The narrative crisis imposes a set of normative judgments about which of these “facts on the ground” constitute problems and a set of normative “plausibility constraints” around potential solutions.

Deepseek and tariffs have halted the tech sector’s meteoric rise: The first kneecapped the growth potential of tech stocks and the second took a sledgehammer to the economy writ large—and to tech hardware supply chains specifically. But Employ America judged earlier this month that “tech still remains the obvious outperformer. This dynamic continues to make tech the kingmaker of capital markets.”

Indeed, the technologies we’re calling “disruptive” today aren’t all that new. Oil and gas drillers have been experimenting with fracking technologies since the early 1900s—but fracking only “disrupted” the global energy market in the 2000s when the circumstances were just right. Some oil drillers discovered geologic hydrogen deposits in 1987 in Mali—but, having no use for it when they did, plugged up that well for two decades. Photovoltaic solar and lithium batteries have long experimental histories, too, but they’ve only recently transformed our energy systems. Perhaps to the chagrin of a speculative equity investor, disruption isn’t an inherent property of any technology—it can only be judged after the fact—but it can be engineered. Cheap narrative hooks are no substitute for the market-shaping work that scaling up anything requires. On their own, they disrupt nothing.

This is not a fixed dichotomy. There are lots of financial products that straddle the boundary between debt and equity (e.g., hybrid capital!), for example. But, in a more generalized sense, debt requires hope as commonly understood, too. Whatever, whatever—I won’t go into this now.

“girl, the tariffs”

Thought-provoking post!

One objection, though. It's not quite right to infer that the shale boom was unprofitable solely on the basis of a long run of years with negative free cash flow (FCF). Because FCF is net operating profit minus capital expenditure, negative FCF could be caused by either 1/ low net operating profit or 2/ high capital expenditure.

In the case of shale, it's probably the latter. All that growth has to be financed somehow!

And indeed, the shale industry in recent years has decided to pull back on investment, and they're now showing enormous positive free cash flow

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-05-05/u-s-shale-s-cash-bonanza-is-about-to-wipe-out-300-billion-loss