Uncertainty is the only certainty

The “real options approach to investment” in the harsh light of liberation day.

I don’t read the Dallas Fed surveys (energy, services) or the latest ISM report on manufacturing for the numbers. I’m there for the quotes, and, this month, “uncertainty” is everyone’s favorite word. Nobody knows what’s about to happen next. All we can collectively agree on, as measured by the stock market’s most precipitous one-day drop since 2020, is that it’s not looking good. Happy liberation day, by the way.

There are lots of pieces covering the impact Trump’s tariffs will have on the energy transition. Hint: it’s bad, bad, and—you guessed it—bad. It doesn’t look good for oil and gas, either; tough times all around. And combined with the massive uncertainty surrounding the future of government spending on energy-related grants and loan programs, not to mention the cuts in headcount and the decapitation of key public agencies like the Tennessee Valley Authority, the “fork in the road” is beginning to look a lot like a fork in the power outlet for our decarbonization goals.

After the tariffs were announced, and after having skimmed much of the subsequent commentary about what we know and what we still don’t know, I think that it’s fair to should assume that, so long as these tariffs stick around, it’s going to get a lot harder to build things in this country.1 Even if oil and gas prices themselves fall (oil is falling, gas may not), and despite the exemptions on many energy-related imports, the prices of many other intermediate inputs will skyrocket and production will stall. Liberation day looks poised to fetter the growth of fossil fuel infrastructure, renewable energy, housing, advanced manufacturing—you name it.

There’s a lot of news about the sectoral impacts of liberation day reciprocal tariffs. But given the list of exemptions, and given the tariffs that Trump already placed on China and on steel and aluminum, I thought I’d scope out what liberation day actually changes for the supply chains I care about.

Let’s look at solar. It always made sense for the solar industry to worry about liberation day. While domestic solar module production capacity is enough to meet U.S. demand, the solar cells that make up those modules are, for now, almost exclusively imported, particularly from Southeast Asia. And there are currently only two domestic production lines for the polysilicon wafers that make up solar cells. The U.S. still has an import kick.

But liberation day turns out not to be an existential threat to the solar industry. The import of polysilicon for the silicon wafers that make up those solar cells is, for now, exempt from liberation day’s increased reciprocal tariffs, blunting the possibility of any price spike beyond the normal tariff rates on imported cells and wafers. In fact, tariffs might, on balance, incentivize the expansion of domestic cell and wafer production capacity, especially now that U.S. module manufacturing has scaled up. The existential threat to the domestic solar supply chain was always—don’t let anyone forget it—Trump’s state-side moves to gut the Inflation Reduction Act and cut off federal supports for clean energy-sector manufacturing.

He’s already moving to kill that baby in its cradle:

Fewer than half of the factories that were expected to come online this year to make components for solar, wind, electric vehicle and batteries are expected to open on time, according to estimates by BNEF, a consulting firm. … Companies have canceled almost $8 billion in clean manufacturing projects so far in 2025, up from $1.6 billion over all of 2024, said Tom Taylor, an analyst at Atlas Public Policy. … But clean energy companies said they are watching Congress closely before signing off on new investments. Heliene, a Canadian solar-panel-maker, has plans to partner with an Indian company to build a U.S. cell factory. But the company is holding off on making the investment until it’s clear that Congress won’t rescind the IRA tax credits, said CEO Martin Pochtaruk.

Canary Media has a similar story focusing particularly on solar cells:

Some companies are thus holding back on solar-cell factory investments until they see what the Trump administration does with a key manufacturing tax credit, which has proven vital to secure construction loans. … The current uncertainty, though, is at the very least delaying the commitment of more private funds to build solar-cell factories.

There are only a handful of solar-grade polysilicon wafer producers in the U.S. They will all benefit from their eligibility for the 48D investment tax credit in CHIPS. And one other company seems to have received federal support for building a polysilicon wafer fab through the 48C tax credit program, although news on its progress since has been scant. Strip those credits away might change picture for the worse very quickly.

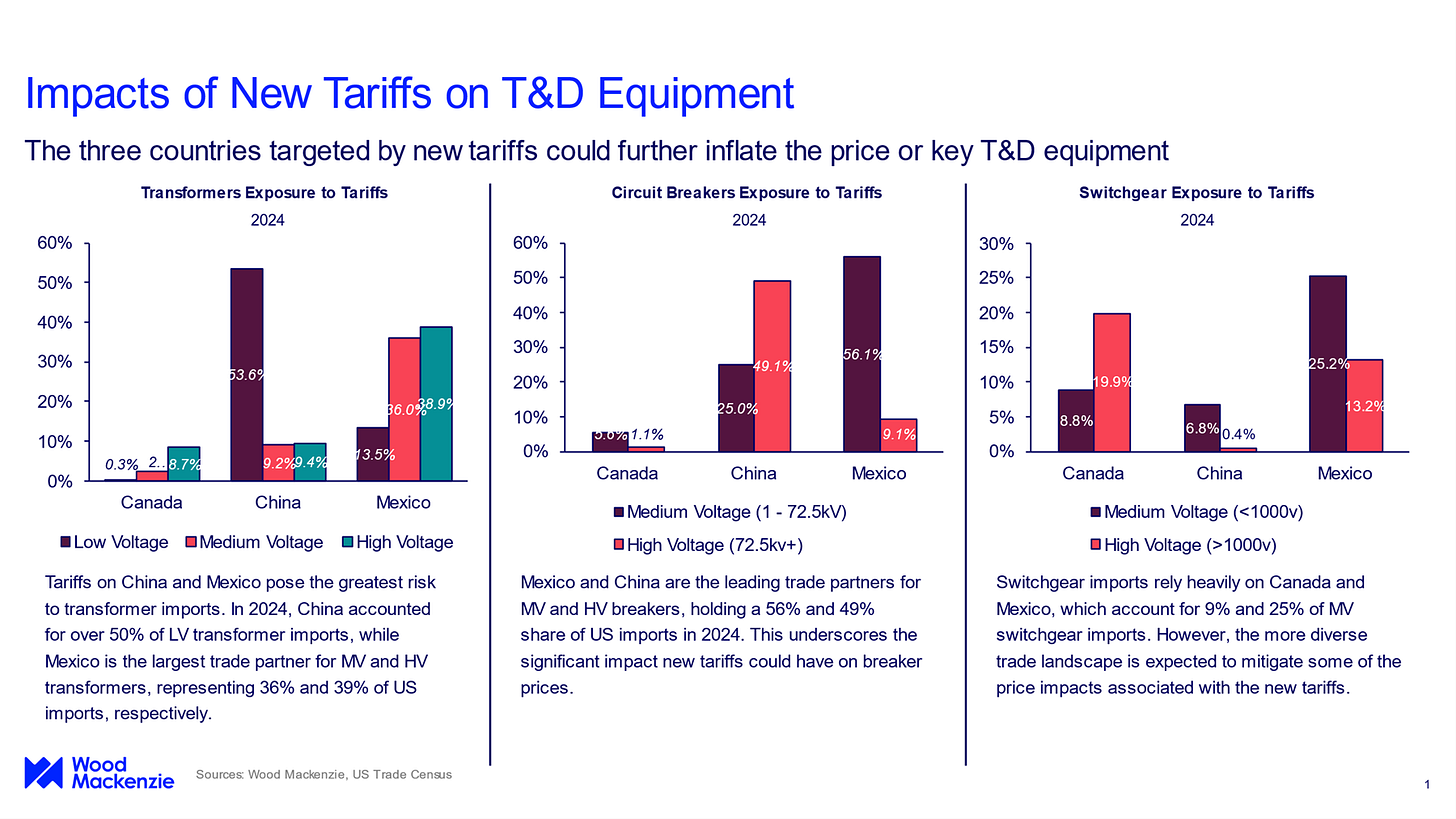

Look beyond the solar module manufacturing chain itself, however, and tariffs remain a real challenge for everything else involved in the installation of solar energy around the country. Tariffs on steel and aluminum, announced in February, will still increase the cost of installing solar modules. Copper, while exempt from tariffs for now, is also skyrocketing in price. And grid equipment such as transformers and switchgears—which use steel and copper—are mostly imported, to say nothing of the shortages that already exist in those sectors.

From WoodMac in January:

From Politico:

The U.S. imported $31.3 billion worth of wire and cable in 2024, and 52 percent came from Mexico, according to Ken Roberts, the chief executive of WorldCity, a data-tracking firm. Another $29.2 billion worth of power supplies and transformers came in last year, with 21 percent coming from Mexico and 13 percent from China. And $13.3 billion worth of electric motors and generators were imported, with 32 percent coming from Mexico and 13 percent coming from China. …

In the utility industry, it will take years for manufacturers to bring new factories online needed to make equipment such as transformers and circuit breakers, said Rob Gramlich, president of Grid Strategies … Expecting companies to bring enough manufacturing capacity online to keep up with growing electricity demand projections “is just not a reasonable timeframe to plan more facilities,” he said. “I think the tariffs are mostly just raising the cost to U.S. utilities and then their rate payers.”

Solar energy is thus caught in the triple vise of (1) transmission grid component shortages, (2) tariffs on imported intermediate goods, and (3) threats to tax credits and other federal programs supporting both input production and final product installation.2 (There’s also the possibility that imported solar energy components will remain cheaper to buy than domestic components, even after tariffs. Can’t kick the import kick that easily.)

And insofar as grid planners should ideally balance solar energy with utility-scale battery storage, well… the outlook there is a lot worse, even if it follows the same dynamics:

Yet the majority of America’s lithium-ion batteries are still imported, and 69 percent of those imports came from China in 2024, according to BloombergNEF. Mr. Trump’s latest round of tariffs, when combined with earlier trade moves, will impose a 64.5 percent tax on grid batteries from China, and that rate would rise to 82 percent next year.

“This will throttle U.S. energy storage deployment,” Jason Burwen, vice president of policy and strategy at the battery developer GridStor, wrote in a social media post. “Bad for business, bad for grid reliability.”

To be sure, some battery mineral components remain exempt from tariffs—but just as many aren’t. We’ll see how battery production and installation prices move in response. But the tax credit story is still the same: withdrawing the benefits of the Inflation Reduction Act would throw the nascent American battery supply chain even further out of whack.3

Investment under uncertainty

This interplay between tariff uncertainty and tax credit uncertainty across the clean energy sector has me thinking about investment theory itself: How should we conceptualize what pervasive uncertainty actually does to change market actors’ capital planning and investment decision-making?

At this point I should mention that uncertainty is not the same as risk. This is Frank Knight’s distinction, and it’s gotten a lot of mileage over the last few years (as it should!) from policymakers who have grown more interested in industrial policy and decarbonization. My colleague Yakov Feygin once distinguished the two thus:

As Keynes pointed out in the General Theory, investors can assign probabilities, and prices, to risk, but not to uncertainty. Measures and perceptions of risk inform how investors distribute capital across their portfolios of investments, but uncertainty determines if investing in a certain asset is even an option.

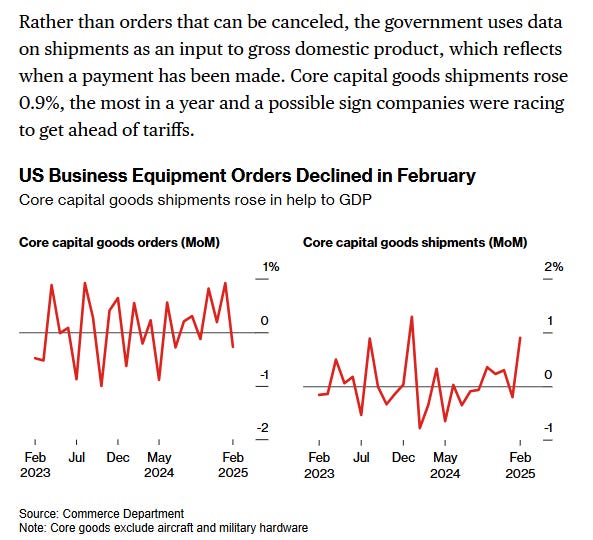

The tariff rates that the Trump administration announced were not what any market actor expected; they caught the entire business community by surprise. It’s abundantly clear that Trump’s tariffs were always uncertainty, not risk. The economic survey data suggests that everyone’s sheer inability to predict how tariffs could affect them has stalled investment. (The only numbers going up in the latest ISM—yes, I admit I did also glance at the numbers, not just the quotes—are prices and inventories.)

From Bloomberg:

So this is what happens to investment under conditions of immense uncertainty.

Apropos of seeing this kind of data pop up everywhere over the last few weeks, I opened Avinash Dixit and Joseph Pindyck’s all-too-appropriately named Investment Under Uncertainty to reread their “real options approach to investment.”4 I love their mental model for thinking about investment: The decision to undertake capital expenditure is functionally an options contract; exercising the “option to invest” is a sunk cost that entitles a firm to some stream of future returns—but choosing when to exercise the option is entirely the firm’s choice, and exercising the option is a sunk cost that “gives up the possibility of waiting for new information to arrive that might affect the desirability or timing of the expenditure.” None of their thinking is very Keynesian, and it gets pretty mathy after the introduction to the book, but I still think this framework works pretty well for thinking about the barriers to capital expenditure as understood by those responsible for undertaking it: investment is irreversible and has a fundamentally uncertain payoff, but firms always can control the timing of that investment. (I don’t think Keynes would disagree here.)

The threat of tariffs highlights how all of these factors operate in tandem. As Reuters put it in early March, a month before liberation day:

In recent weeks, some companies raced to get ahead of tariffs with pre-ordering of goods, but executives have until now been taking a wait-and-see approach on investments and expenditures. … “The uncertainty continues,” said David Young, an executive with the Conference Board, a global business group. "There are decisions being postponed and delayed ... there very much is a degree of paralysis."

The dynamic here is plain to see: companies are holding off on taking irreversible investment decisions in order to wait for more information that might help dispel the uncertainty around the impacts tariffs might have on their profit margins.

In line with Dixit and Pindyck, I think Trump’s war on domestic spending—through both tariffs and his gutting of government—has three key consequences. First, a whole lot of “options” to invest are now “out of the money,” insofar as the value of those investments as determined by their expected revenue streams—if those can even be quantified—fall below the upfront exercise price and lose their intrinsic value.5 Even still, firms may choose to decline to exercise options that remain “in the money,” “because by exercising it the firm gives up the opportunity to wait and avoid the loss it would suffer should the value fall.” There might always be more tariffs, after all, and we might lose the Inflation Reduction Act, too. This is also why firms have hurdle rates: “Only when the value of the asset rises sufficiently above the exercise price—the option is sufficiently ‘deep in the money’—does its exercise become optimal.”

Second, tariffs have made the total cost of an investment fundamentally unpredictable—unknowable, even. What do firms do when the total cost of their investment is unknown? Dixit and Pindyck have the scoop: “information about [the total cost] will be revealed only as the first few steps of the project are undertaken,” but each step is itself an irreversible decision that firms might be loath to make. While Dixit and Pindyck reasonably assume that firms might still find it “desirable to start the [multi-stage] project even if orthodox NPV is somewhat negative,” I’d counter only half-jokingly that this is the United States, not China; investment here focuses far too much on short-term equity returns to the detriment of long-term market share.6 If we don’t know what anything costs anymore, and if no market actor is going to sacrifice its liquidity to irreversibly attempt cost discovery through a series of stepwise investment decisions, and if everyone else is waiting for someone else in the economy to give them the information they need…

That brings us to the third consequence, hysteresis. Keynes’s notion of hysteresis being path-dependent is pretty similar to Dixit’s and Pindyck’s. Failing to invest is itself an investment decision—and a pervasive, economy-wide failure to exercise options ends up seeing those options “expire,” as it were, as supply relationships and offtake contracts break down, workforces disband, and plant depreciates across whole sectors.7 This is the story of the Great Recession—but this time with tariffs: Even if the underlying causes of a demand shock like a global financial crisis or Trump’s tariffs are reversed, the investment decisions themselves may not reverse.8 The firms that could make them might not even be around.

Fog of trade war

Dixit and Pindyck’s “options approach to investment” really only formalizes what we’ve probably intuited about the impacts of Trump’s tariffs and his economic policy writ large. Everything’s uncertain and worse now; lots of options to invest are falling “out of the money”—and it’s hard to tell what, if anything remains “deep in the money.”9

Speaking as someone who runs extremely back-of-the-envelope financial models for energy projects, it makes me feel crazy to look at estimates for overnight costs of capital—the keystone cost measurement in my project finance models—and to realize that I might as well throw these numbers out the window. It’s not just cost measurements, either. Financing assumptions including interest rates and loan terms are likely to shift for the worse. And project development assumptions regarding PPA price inflation rates, maintenance costs, interconnection costs, and insurance costs are all increasingly unpredictable. To be sure, I’m also making imprecise assumptions about some of these variables, especially when I need to make a quick sketch of the conditions under which certain kinds of projects will pencil. So long as the rest of the model uses precise and credible assumptions, it’s more okay. But now I can’t count on that! Of course, there will always be gaps between models and the reality they’re aiming to describe—but my faith in the ability of the models I use to be at least directionally correct about energy projects’ financials is wavering.

I imagine this is what’s happening to most businesses’ CFOs in real time. I bet they’re telling their employees to halt input purchases until their lawyers and accountants can do the math on tariffs and call up their usual suppliers to check for price quotes. The CEO of the American Clean Power Association puts it nicely: “If you don’t know if the inputs to your factory are going to dramatically increase in price — it slows things down.” There is a meaningful difference between saying that you expect that input prices will rise dramatically and saying that you don’t know if those prices will rise dramatically. If tariffs have unmoored even key industry lobbyists from their own price expectations, and if this is happening all at once across the entire economy, even in sectors that seem entirely disconnected from tariffs,10 then to say that tariffs slow down investment is a colossal understatement of what we’re about to see happen to our supply chains. Tariffs like these aren’t a material repricing of the economy so much as they they threaten a widespread de-pricing of the economy.

The coming demand shock to the U.S. economy will undoubtedly break some supply chains—for example, is this the end of the American EV industry?—and will degrade the economy’s productive capacity; this much we know. But Dixit and Pindyck’s options approach, which envisions the economy as a series of sequential capital expenditure decisions, is a working and compelling toy model for understanding how that might happen from the perspective of capital planners themselves. The “de-ranging” of supply chains we’re about to see will make it difficult, if not impossible, to project plausible or even remotely precise cost estimates for lots of multi-stage investments. We already see this dynamic in the American nuclear industry, which has seen only one new nuclear reactor project completed in the past three decades. Now imagine this across the whole economy: cost overruns relative to cost baselines that were uncertain in the first place and delays from supply chain quality and capacity issues will complicate capital planning for a whole host of technically complex but otherwise-once-predictable investments. In a situation like this, could anyone blame private developers and investors for raising their hurdle rates, risk premia, and margins? Most market actors will flee to safety at the cost of building the necessary industrial capacity, and it would be rational to do so.

This framework can apply to any major shock, that’s true. But I think that this combined tariff-plus-budget shock might have worse effects than the pandemic-related “sudden stop” to markets in 2020 ever did, even if the measured GDP effects seem smaller, for two reasons: not only is tariff policy subject to Trump’s personal whims,11 but Congressional budget horsetrading could break both old and new parts of the American financial sector. Tax-exempt municipal bonds, for one, were never safe from the Trump administration—but what happens to clean energy project development if Republicans take away the investment tax credit or tax credit transferability wholesale, or if they forcibly retrench Fannie and Freddie? Unlike during the pandemic, the government wasn’t playing jenga with the financial building blocks of key industries in real time.

It’s a sad irony that the only way to mitigate this all-encompassing uncertainty is to spend through it, to use procurement and market-shaping to re-establish supply chains and create plausible ranges for input prices that other market actors treat as credible. The only entity that could plausibly do this at the scale required to stitch supply chains back together is the federal government12—which seems pretty reluctant to “spend through it” in a way that might retroactively give the tariff strategy even a semblance of political economic coherence. The Trump administration is making it such that ambitious investments are unquestionably out of the money, and—soon enough, at this rate—we’ll be out of money, too.

Tariffs are sabotage? It’s more likely than you think; Veblen, like a good progressive in the age of William Jennings Bryan, didn’t like trade restrictions much.

In the fallout from liberation day, First Solar was the only renewable energy company that saw its shares rise. The rest of the renewable energy sector slumped, and manufacturers of key components expect costs to head higher. But Heatmap agrees with me that “If [the IRA’s] tax credits are at risk, then First Solar may not be a winner so much as the fastest runner ahead of an advancing tide.”

In the whirlwind of news about the “external revenue service,” don’t forget to ask how the internal revenue service is doing.

Given the circumstances, choosing not to read a book literally titled Investment Under Uncertainty seems like a dereliction of duty.

It’s not that “out of the money” options will never be profitable, but these options have no intrinsic value in the present absent a major positive change in the information landscape or in the certainty around its future cash flows.

The pervasive unknowability of many projects’ total costs is undoubtedly one of the key investment barriers threatening a certain much-discussed agenda that’s in the discourse.

As Dixit and Pindyck put it, “a substantial part of [firms’] market value is attributable to their options to invest and grow in the future, as opposed to the capital they already have in place.” Economic shocks can put all those options to invest “out of the money.”

It’s funny: Dixit and Pindyck take hysteresis and path-dependence seriously, but they’re neoclassically minded enough say things about “averaging over good times and bad times” in the economy as if that were actually possible to do.

If anyone has guesses, I want to hear them.

Klarna, the pay-in-installations company, is postponing their IPO because of tariffs? I suppose this makes sense: a bad stock market is bad for any business looking to use it.

And the whims of large language models, apparently? We’re in the stupid timeline.

Tim Barker’s description of one World War I-era proposal for an economy-wide cost insurance program seems appropriate to mention here.