The derisking debate will continue until morale improves

Why does the IRA taste like cilantro to some and like soap to others? And what does that have to do with “derisking”?

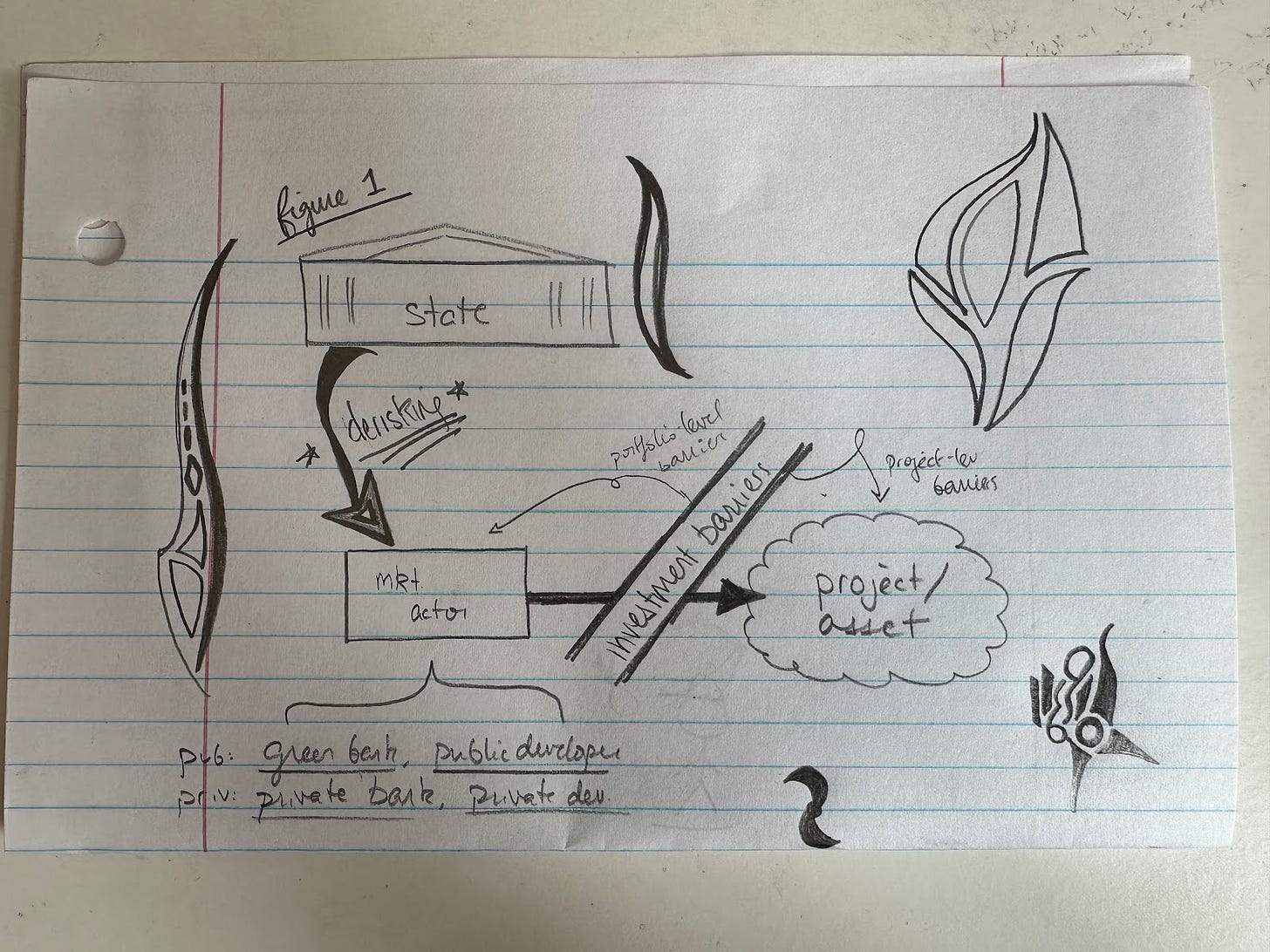

image: my very stylized and underspecified sketch of how derisking works(?).

August 19, 2024

Will we really have the “derisking debate” on Twitter every summer? Maybe we should―it’s helpful to see where people stand. Of course, I’m biased, seeing as this year I participated (and found it quite productive). The arguments made this past week were nowhere nearly as detailed as those from last summer’s showdown, hosted in the Phenomenal World theory thunderdome. But, once again, the Inflation Reduction Act is to blame for getting us all riled up. And that’s worth commenting on: Why does the IRA taste like cilantro to some and like soap to others? And what does that have to do with “derisking”?

Even if anyone nitpicks the kind of green transition the IRA envisions, I don’t think that means they are debating the merits of the IRA’s industrial policy vision in bad faith, as if they want the IRA to fail. Let’s not assume that about anyone here. But this most massive climate spending package has very clearly become a Rorschach test for the industrial policy left. Many of us have good reason to argue that the sheer volume of spending in the law heralds the emergence of the American “big green state,” however patchwork and incomplete that may be; call this Team Transformative. And many of us believe the IRA, on its own, will fail at decarbonization due to its accommodation of and subsidies for unaccountable and uncoordinated private market actors, even if it comes with carveouts for the public sector; call this Team Inadequate.

This disagreement is about what we think is politically possible to achieve under current conditions, and, suffice to say, I think both perspectives have their merits. I’m big on a “both-and” reading here; things are allowed to be both transformative and inadequate at the same time, even if you’re not into dialectics. What I’m really curious about is how the derisking debate fits into this Janus-faced understanding of American industrial policy.

“Derisking” is a term of art in the policymaking world, brought to wider twitterati attention by Daniela Gabor, that generally refers to any process whereby the state produces investability for other market actors. More practically, derisking is when the state shoulders the risks that investors might face when choosing to undertake an investment. (More on this definition later.)

The topic du jour―du semaine, I suppose―is this widely shared Financial Times article about how delays plague IRA-enabled investments. To anyone on Team Inadequate, the piece is a laundry list of the limits of derisking private capital. The FT provides some evidence: “Companies said deteriorating market conditions, slowing demand and lack of policy certainty in a high-stakes election year have caused them to change their plans. … But a tough macroeconomic backdrop, combined with overproduction in China, slowing demand for electric vehicles and policy uncertainty has chilled further progress.” The IRA’s reliance on derisking private investment through subsidies and concessional finance, not to mention the law’s commitment to “mobilizing private capital,” in its pursuit of American industrial transformation will inevitably fall short given private investors’ reticence in the face of these conditions. The obvious solution here is to cut out the fickle private investor and get this done through the state, through a massive public investment program.

I’ve made this argument myself before! With a healthy respect for the fact that the private sector has its particular strengths, I think it’s hard to disagree that private investment alone won’t cut it. The state is going to have to get involved to a massive degree in order to really deliver solutions at scale.

To anyone on Team Transformative, however, this argument does not invalidate the direction and magnitude of the IRA; rather, it may even reinforce the IRA’s potential. The IRA has substantial carveouts for public sector-led development, elective pay and the LPO’s Title 17 appropriations chief among them. The IRA really does help level the playing field for the state in ways that we have not really seen in decades, laying the groundwork for the public sector to actually begin cutting out the fickle private investor. In fact, I’ve made this argument before, too.1 In this telling, the FT piece, rather than showcasing the limits of “derisking,” presents evidence of inadequate state capacity and the growing pains of building it: “Some of the delays are policy driven. Slow government rollout of Chips Act funding for semiconductor projects and lack of clarity on IRA rules have left a number of projects at a standstill.” And White House official Alex Jacquez hits on related obstacles: “We continue to work to clear barriers related to permitting, to financing, where they exist.” Jonas Nahm highlights that delays are likely when so many market actors are competing for domestically produced clean energy components, particularly in a supply chain otherwise dominated by China.

The implication here is threefold: (first) despite the fact that the IRA puts us on a pathway toward a bigger green state where the public sector can support the green transition, (second) the public entities delivering the green transition would nevertheless be staring down the barrel of these same problems―meaning that (third) the state would still need to produce investability for the public-sector actors charged with greening our economy.

This was basically my take, inspired by a great thread from Manasi Karthik. In the process of staking my claim, I said something controversial: the US federal government needs to better derisk the public sector institutions leading the green transition. I cited CPE’s latest work on how Treasury and HUD are very clearly derisking state housing finance agencies’ interest rate risks through what’s essentially a rate hedging product; it’s no secret I think we should do this for more things we want public agencies to build. The public sector needs derisking!

Daniela Gabor countered: “Public to public is not derisking.”

I disagree. In my own words, “if derisking is the process of governments ‘producing investability’ for other market actors, and if governments themselves are market actors, then public-public derisking is possible. In my opinion, there's a ‘it's only champagne if it's from the Champagne region of France’ view built into restricting the term derisking to refer only to public production of investability for private actors―which is fine, I think, but not my way of thinking here.”

This “producing investability” definition has precedent in last year’s derisking theory thunderdome; in other words, it didn’t fall out of a coconut tree. (Chirag Lala and Karthik both agreed with my general assessment.) I’d say that the “production of investability” here encompasses any action that governments take to reduce or eliminate the potential that an investment, if undertaken, fails to yield some threshold level of returns that keeps the investing entity financially unharmed. To be sure, this definition is porous, insofar as derisking comes in many forms and might fail. But it allows for the fact that public investors can set lower threshold returns while having higher thresholds for what constitutes financial harm―yet acknowledges that both public and private investors can face similar barriers even if they do not share the same tolerance for risk-taking or for bearing fundamental uncertainty.2

That’s why I remain convinced that derisking is a process regardless of whom it’s directed at. I sketched it out here, below. If market actors face investment barriers, and if public sector entities are market actors, then they must face investment barriers, too. If derisking is about eliminating those barriers, then derisking can apply to public entities. (“If it walks like a duck and it talks like a duck…” You know how it goes.)

But I think the better way to stress my argument is to turn this into a two-step process. The next figure, below, is essentially what the IRA does for green investment: the federal government, through the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, the LPO, and elective pay, juices the potential of state green banks, which are looking to drive investment into decarbonization-related projects. They need liquidity to be ambitious with their portfolio creation; the federal government provides it, and in doing so helps eliminate some of the portfolio-level investment barriers facing public sector green banks. But none of these green banks are restricting themselves to financing solely public or private project developers―I would know, I work with them. Both public and private project developers face project-level investment barriers, including local permitting and regional transmission regulations, not to mention delays and construction (bridge) financing. These investment barriers are universal; even if a public sector entity could in theory receive cheaper bridge financing, some other entity needs to provide it on decent terms, and even if a public sector entity could get a project permitted, it would need to receive speedy interconnection onto the transmission grid.

There’s no reason to me why green banks supporting a public project through their increased liquidity and their administrative capacities wouldn’t be derisking when they would be doing very similar things for private projects.

Essentially, this is why I believe that my weaker, process-based definition of derisking is analytically more useful than a stronger, participant-restricted definition of derisking. My work on IRA implementation leads me to believe that the actions the government must take to build a “big green state” are not mutually exclusive from policies that “derisk” investment. Regulatory certainty around transmission and grid interconnection is important for everyone, and municipalities setting up virtual power plant programs deserve liquidity as much as, if not more than, private solar module manufacturers do. To make the argument that state-led investment does not also involve producing investability is, simply on its face, incorrect.

But it’s worth considering why Gabor disagrees with me and Karthik. It’s about more than the definition: “you're both treating derisking as a technical engineering investbility concept, without (distributional) politics. Once you factor that in, building stuff through and within the state is different from co-producing asset classes for financial capital.”

She’s definitely right about the first part: speaking for myself, I certainly am treating derisking as a technical process of making a project or asset investable, without baking the distributional consequence of that action into my definition. But I think that’s fine.

Derisking as a policymaker-made term of art, from the world of technocratic financier types trying to “mobilize private capital,” is definitely not going to hint at distributional consequences. Then again, why should it? Concepts like state capacity, debates around the nature of discipline, and questions around the proper role of bureaucrats and how they interact with the private sector in a developmental state all already have a long pedigree in our field; we can use these frameworks to equal if not greater effect.

Judging the distributional consequences of a derisking strategy is analytically distinct from describing how that strategy works, particularly because distributional outcomes are affected by many other factors that may not have much to do with investment policy. In fact, I think that our goal should be to connect derisking to distributional policy rather than assume that derisking has a given distributional effect: as policy thinker types, we should be capable of coherently describing why certain investment policies shape the green transition positively and why others don’t, regardless of the actors involved. For example, I think it is irresponsible for the Connecticut Green Bank to use Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund cash to derisk the ability of local lenders to offer rooftop solar and energy efficiency loans to homeowners, because it avoids building loan servicing capacity for low-income customers within the Green Bank itself, instead letting local lenders set their own independent underwriting criteria. It makes no sense here not to centralize the criteria and capacity for asset management under public aegis. But I think derisking the production of batteries and solar modules through the IRA’s expanded manufacturing tax credits has been a smashing success insofar as it actually shifts our technological frontier and makes it easier for the Connecticut Green Bank to procure solar panels in the first place. Derisking, whether for program administration or capital expenditure, is a process, but that doesn’t mean it’s neutral.

The state does relate to risk differently than private actors do―lower hurdle rates, public mandates, access to greater liquidity and longer-duration financing, the whole nine yards―and, in these cases, derisking undertaken by the public sector for the public sector is meaningfully distinct from derisking undertaken for the private sector. And I feel confident that Gabor agrees with this, at least based on what she said last summer, that “there are different kinds of pathways to changing behavior of private capital,” one pathway involving public-sector actors dominating decarbonization-related sectors. There’s a kind of division of labor between state and capital; the state should not let capital do its job.3

Still, she sees derisking as a fundamentally macrofinancial issue concerning the creation of investable, bankable assets for private investors within the larger systemic constraints of monetary dominance by central banks concerned about prudential risk management. In this light, the IRA feels kinda orthogonal to macrofinancial policy: the law’s climate provisions are designed primarily to juice fixed investment, and only secondarily to create bankable assets for private investors, even if those processes are connected. This distinction, more than anything else, differentiates the IRA from the kind of financial derisking that remains hegemonic in international development finance―which Gabor, correctly, takes deadly aim at in her “Wall Street Consensus” paper.4 Everything I’ve seen from the world of international development policymaking confirms that the derisking strategies there really are intended to induce institutional investors to enter Global South markets as if that outcome is the key to decarbonization. The IRA, on the other hand, talks a big game about mobilizing private investment but has a telos fixated on deployment rather than on investor portfolio construction.

That’s not to say that investor portfolio construction doesn’t matter here. In fact, even this distinction between macrofinance and fixed investment is theoretically fuzzy to me: if there’s no analytical difference between, on one hand, investing in a financial asset that yields a somewhat-predictable stream of cash flows and, on the other, investing in capital goods that also produce stuff that yields a somewhat-predictable stream of cash flows when that stuff is sold, then there should not be anything stopping us from using the language of derisking to describe how the IRA works.

To be sure, fixed capital expenditure faces a different set of investment barriers than financial assets do. That’s why financial derisking strategies like, say, loan guarantees or tax credits, might on their own be incapable of getting projects built. How investors treat tax equity and transferred tax credit assets varies with macroeconomic conditions, and it’s worth scoping out how downstream project deployment is affected by changes to tax credit structures, and why.5

Even viewing the IRA through its relationship to the central bank, it’s obvious to see how monetary dominance―the Fed’s control over interest rates, not to mention its control over which assets receive a “high quality liquid asset” designation―screws both the public and private sector’s abilities to contribute to the IRA’s policy goals. It’s theoretically possible, although messy, to undercut central bank rates with credit guidance, or lower “green interest rates,” for public developers―and, to be clear, that would be derisking―but, under the current macrofinancial regime of independent central banks, the entity offering those concessional loans would ultimately need access, directly or indirectly, to the liquidity support of none other than the central bank in order to stay afloat. In this sense, Gabor is right that the IRA won’t go far enough at shifting the fundamental constraints on state spending.

But I don’t want to see anyone dismiss the IRA entirely on those grounds. Skanda Amarnath put it well last summer when he argued, like me, for treating derisking as a process rather than a normative thing: “My biggest concern with painting things with a broad derisking brush is that there are definitely examples where derisking can go wrong, but there are also places where it has a legitimate purpose in the energy transition.” And this is why the IRA is as beautiful as it is frustrating. The law’s breadth allows us to really, truly debate the merits of industrial policy program design at the local, state, and federal levels, even in spite of wider economic constraints like monetary policy.

I would be curious to see how Gabor judges the actual details involved here. Her most recent work on the subject (to my knowledge), co-written with Ben Braun, fleshes out the difference between the big green state and what she defines as “robust derisking.” She and Braun argue that a regime of robust derisking, exemplified by the IRA, “can mutate into a big green state regime through institutional change that increase the state’s monetary-fiscal capacity to spend and its political-technocratic capacity to plan and discipline capital.” They cite Lala’s work on elective pay as an example of the kind of reform “designed to increase the state’s capacity [for] green fiscal spending and for disciplining capital and scale back unsustainable economic activities.” Politically, I think Gabor’s goal here is clear, and correct: she wants to see American industrial policy move more closely toward disciplining the decisions of private capital. But without engaging systematically with the IRA’s real-time implementation triumphs and stumbles (something which her and Braun’s paper does not really get into), and without specifying why loosening budget constraints on state investment necessarily disciplines private capital, her theory of derisking really feels removed from the reality of how it’s playing out in the US.

The world of IRA implementation is a very “mo money mo problems” kinda situation: precisely because there’s so much money at stake, policymakers are learning how much reform our permitting, siting, and transmission processes really need, and they’re growing aware of the challenges of relying on tax credits as our chief source of subsidy. And hopefully we can also acknowledge that we should be careful about how our emerging green banks work with existing lenders. Through this whole process, American government institutions at all levels are building capacity, however slowly, to enable investment, public and private. Frankly, I don’t see any other way for the big green state to emerge from our current political economic reality. Seen from that light, the term “derisking” remains useful for categorizing the kinds of capacities that both Team Transformative and Team Inadequate might agree are necessary to unlock the investments we need―but that should never detract from a spirited debate over what types of investments in the first place are even useful, or what their distributional impacts are. We can all hash that out next summer.

Thanks to Chirag Lala, Manasi Karthik, Melanie Brusseler, and Yakov Feygin for substantive engagement with this very slapdash argument.

footnotes

Different public actors face different tolerances, too. For example, American munis and emerging market economies alike are afforded less liquidity than the U.S. federal government, and this liquidity hierarchy constrains their ability to budget and spend as their leaders and communities might desire. Yakov Feygin suggested to me that we see derisking as the process of shifting market actors’ budget constraints across sectors and time: “that’s not really de-risking but allocating access to the money printer.”

Thanks to Melanie Brusseler for suggesting that I apply the idea of a “division of labor” here.

I’ve said before that the term derisking “caught on as a rhetorical device for development economics types (the old me included) looking to specify the pathways to privatization or public-private partnerships mostly in emerging markets.” It’s easy to see why! When I present on topics in international climate finance, I always make use of Gabor’s work to structure my arguments.

Melanie Brusseler said something like this last year: “as we move into fixed capital investment, there’s a way to be appropriating this language of derisking. I don’t even know a better term for it.”