LLMs in the art gallery

At the infamous intersection of art and technology―not a fan.

Welcome?

This is the crow’s nest.

First, a justification: If you’ve followed my writing, you might have seen posts I’ve published on Wordpress, where I share my thoughts on climate, the financial system, and political economy. In the past, the best way to get my work out there was to tweet links to my blog. But now Twitter is dying. So I want to share my writing and thinking, however underbaked, somewhere else. This might be the better home for them: everything I already read from writers on Substack suggests that this platform will enable me to flesh out thoughts that are better-formed than tweets but, for the most part, free from the responsibilities that come with writing full-bodied essays.

I’m looking forward to engaging with readers here, perhaps more substantively than I’ve been used to, about all sorts of topics, too—not just my usual climate and finance beats. Now that I’ve justified myself, I feel better about asking you to subscribe here:

LLMs in the art gallery

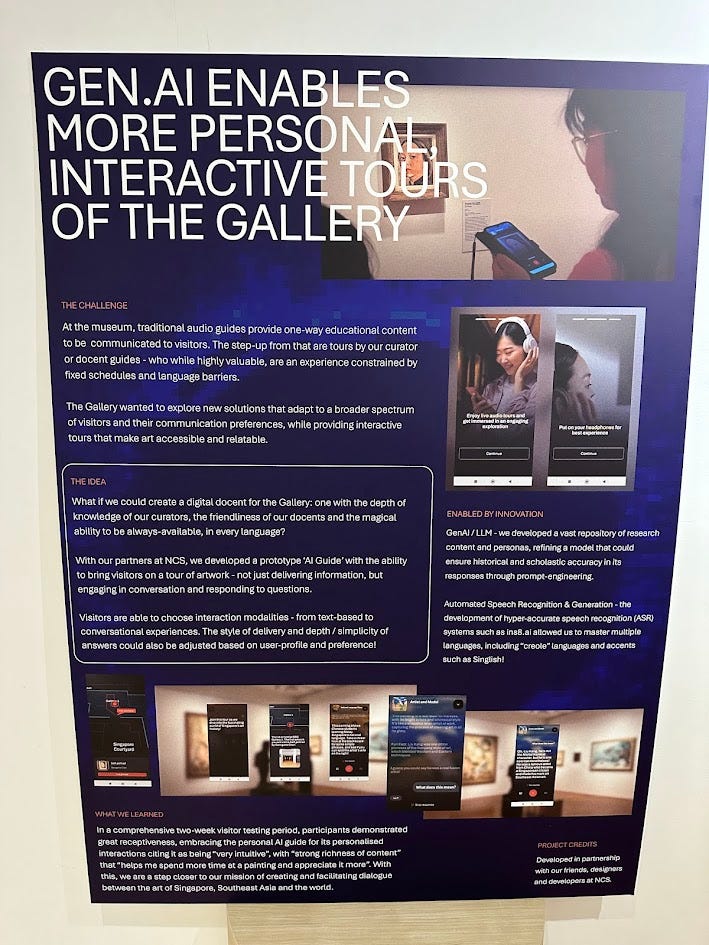

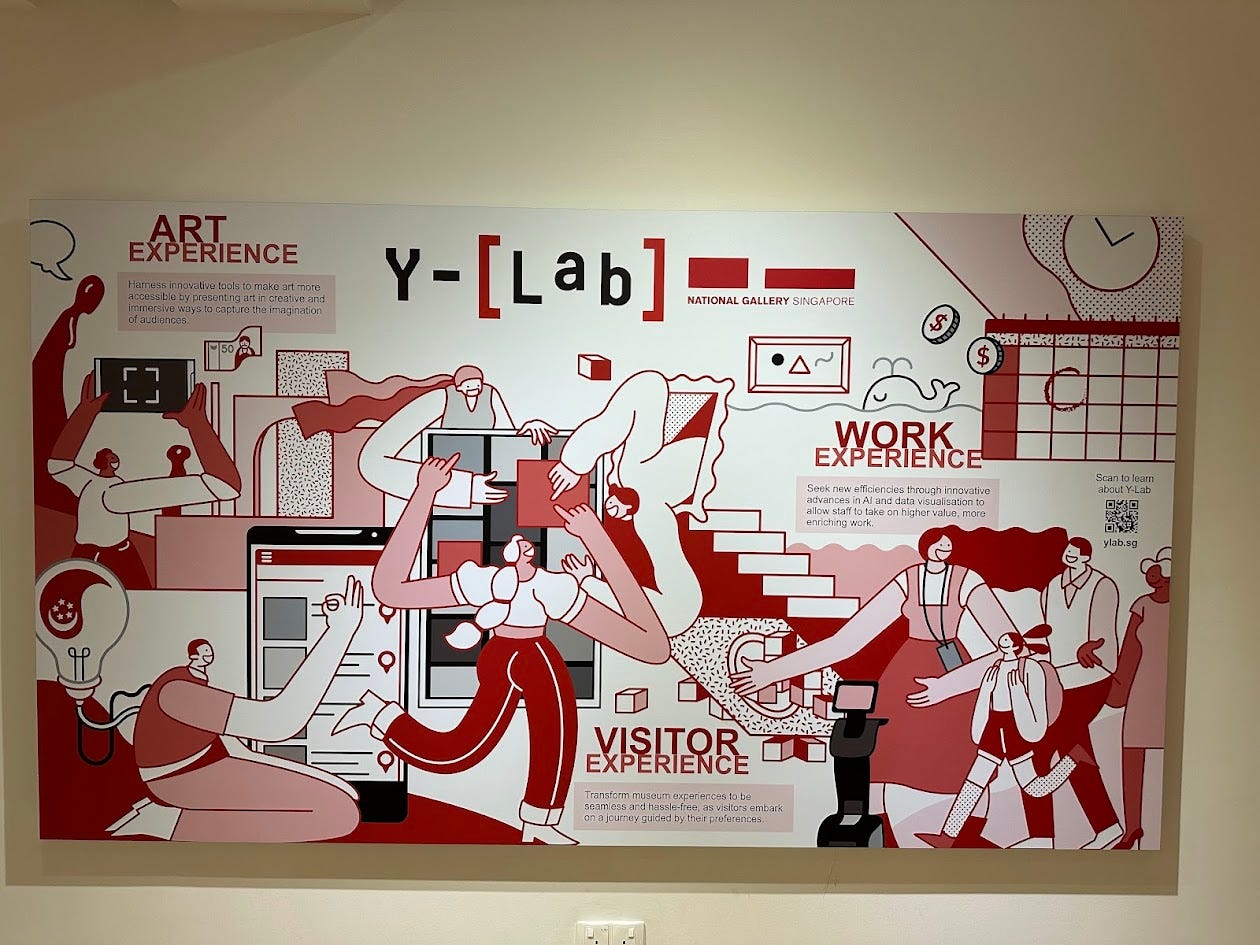

In the basement of Singapore’s National Gallery of Art is the “Y-Lab,” a small white room at the infamous intersection of art and technology. Here, the Gallery’s Chief Innovation Officer and his team display projects that integrate emerging technologies into visitors’ experience of the museum and of the art itself. When I visited the Y-Lab, I found some of the projects displayed super weird―have you ever heard of a “negentropic field” before?―but most were mundane. One of the more predictable projects was a chatbot that visitors could interact with as they stroll past paintings.

Per the poster:

“At the museum, traditional audio guides provide one-way educational content to be communicated to visitors. The step-up from that are tours by our curator or docent guides―who while highly valuable, are an experience constrained by fixed schedules and language barriers.

The Gallery wanted to explore new solutions that adapt to a broader spectrum of visitors and their communication preferences, while providing interactive tours that make art accessible and reliable.

What if we could create a digital docent for the Gallery: one with the depth of knowledge of our curators, the friendliness of our docents and the magical ability to be always-available, in every language?

With our partners at NCS, we developed a prototype ‘AI Guide’ … not just delivering information, but engaging in conversation and responding to questions. … The style of delivery and depth / simplicity of answers could also be adjusted based on user profile and preference!”

I’m mostly inclined to take the Y-Lab’s stated problems with the status quo at face value. Conversations with docents offer stronger opportunities for inquiry and engagement with art than one-way guides do, and language barriers are no fun for anyone. And let’s assume that visitors’ engagement with docents is indeed constrained by fixed docent tour schedules. Given these problems, it’s nice the Y-Lab spells out exactly what could solve their problems: building a friendly, interactive “digital docent” with the “magical ability” to speak your language at any hour of the day.

The Y-Lab seems to present this digital docent not as a 1:1 replacement for audio guides and docent tours but as a third option catering to “a broader spectrum of visitors and their communication preferences.” But who is this “broader spectrum”? As stated on the poster, a visitor who participated in the Gallery’s two-week trial of the digital docent praised the LLM for helping them “spend more time at a painting and appreciate it more.” Even if this is just one single person, that person belongs to a broader category of visitors who, for whatever reason, might otherwise speed past paintings and the placards next to them―which is to say, most people.1 These would be the visitors whom the Y-Lab hopes to draw in with LLMs, which could cater to any schedule and converse with any visitor about whatever they want, “adjusted based on user profile and preference.”

To be sure, I don’t think it’s wrong for anyone to grab a pair of contextual crutches as they walk through a gallery. I want to exercise my critical thinking as best I can, but I don’t really know art history, so I will gladly learn from whoever can teach me. I’m a dumbass―give me the audio guide. In that respect, I think it’s good if an LLM can adjust the depth and simplicity of its responses based on its users’ prompts and knowledge levels.

But I only think that it’s good because I think that any decent docent would need to do the same! And that’s the problem, isn’t it, that the Gallery thinks an LLM is the better investment here? From a labor costs standpoint, the Y-Lab has its justifications. Get a good enough LLM running and the Gallery can support every visitor at once. But when the “digital docent” gets deployed at scale, I suspect the museum will actually be pressured to phase out many of its docent-led tours and its audio guide programming. If the LLM seems good enough to meet the needs of every visitor “adjusted based on user profile and preference,” then there’s just no need to supply as many audio guides or tours. After a point, the art-curious visitors simply won’t have a choice between the three services.

Through ostensibly accessible technology, the Y-Lab promises to “transform museum experiences to be seamless and hassle-free, as visitors embark on a journey guided by their preferences.” LLMs are a sort of Swiss army knife technology that eliminates any mismatch between visitors’ preferences for how they’d like to experience art and their actual experience of the art on display.2 But the perceived frictionlessness―that “all you are sacrificing is your own inconvenience”―merely displaces the real friction of engaging with art: the challenge of knowing what you’re looking at, communicating what’s important about it and what it draws from, and expressing a judgment about it and its relationship to other works.

I left the basement, I went upstairs, I saw some art.

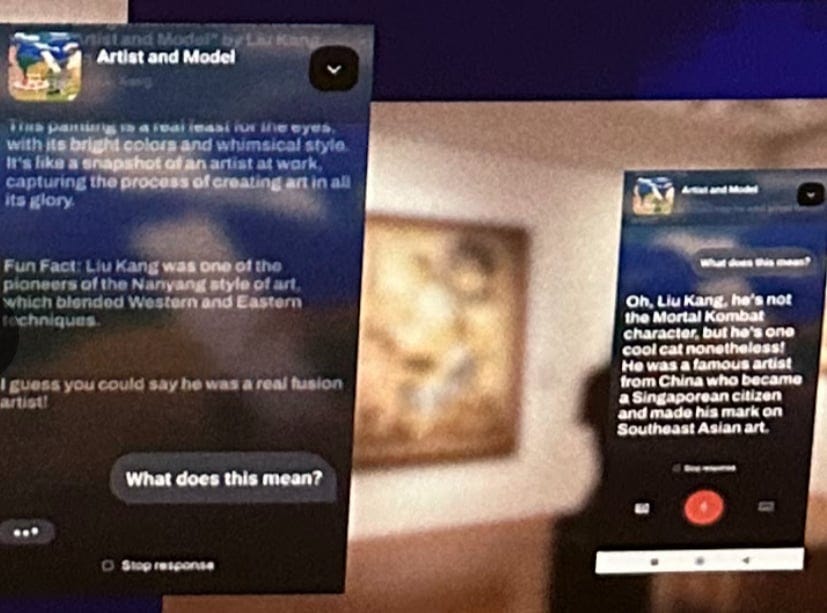

This is Liu Kang’s Artist and Model, one of the Gallery’s more well-known paintings. I loved it for a lot of reasons, primarily how it’s interpreting the challenge of interpretation itself. Liu is looking at his friend and colleague Chen Wen Hsi painting a portrait of an Indonesian model—and is himself painting portraits of Chen, the model, and Chen’s portrait. Liu is painting his understanding of that interpretive space between the three of them: in the gap between Chen and the model is a portrait; in the gap between Liu and both Chen and the model is Artist and Model itself! In those gaps is just as much the potential for beauty as the potential for both refraction and miscommunication. In a way, Liu is explaining painting through painting.

Now, look closely:

Here, I’ve zoomed in on my photo of the poster advertising the “digital docent,” from way above. The pictures at the bottom of that poster explaining how the “digital docent” works caught my eye because the LLM is explaining none other than Artist and Model.

It calls the painting “a real feast for the eyes,” “like a snapshot of an artist at work, capturing the process of creating art in all its glory”—which is all descriptively correct. (Although I’d object to describing this as glorious at all. I think Liu’s and Chen’s trip to Indonesia was a little bit fraught with “Gauguin in Tahiti” vibes.) It also describes Liu as a “fusion artist” whose school of art blended techniques. None of this is information I would have missed if I stared at Artist and Model for a minute and read the placards next to Liu’s works. So, on a substantive level, I don’t think the LLM is telling me anything I wouldn’t otherwise have learned about this piece. I could ask it “what does this mean?”, but I’m not sure I’d learn much from the response.

But I also think the painting itself stands in striking contrast to the LLM being used to read it. In a sense, the LLM short-circuits the work I could take to interpret this painting myself; it eliminates the gap between experiencing the painting and coming to understand it—the same gap that exists between Chen and the model, and between Liu and the both of them. Indeed, the LLM gives us the finished products of interpretation with none of the context that produced it, just as if Liu had never taken the trouble to paint this. The fact that the Y-Lab is using the LLM to explain Artist and Model in particular only seems to strengthen the force of the painting’s central question.

Someone has to do the work of interpreting the art in a museum in order to communicate it; the LLM has to be trained on something before it responds to your prompts. A museum visitor’s apparently frictionless, “optimized” experience of a “digital docent” remains the product of someone else’s extremely friction-ful and likely frustrating engagement with art.

To be fair, this critique applies to a docent tour or an audio-guide, too. But the “displacement” there is not complete; your human interlocutor―an art student, a hobbyist retiree, someone identifiable―is in front of you, and/or in your ear. Pulling out a phone to query a chatbot, on the other hand: whose previous engagement with art are you actually drawing on as your crutch for making the same attempt yourself?

Art galleries are not the only spaces where I find myself noticing this dynamic. Last month, on 730DC (the best local DC newsletter!), I read a news snippet about how one guy with a lot of AI runs a bunch of newsletters across a bunch of cities:

The article itself, by Andrew Deck, is good reporting. This is how the founder of the newsletter network, Mark Henderson, justifies his work:

“Local news should be local. The problem is, at this point, there are economic challenges keeping that from happening. Smaller communities rarely can support enough staff to run a traditional news organization,” said Henderson, who currently runs Good Daily from New York City. “I see technology, and LLMs specifically, as our best shot to fix this.”

Where local news is already going extinct due to lack of funding and the rise of short-form video and podcast platforms, and insofar as hiring local beat journalists is simply uneconomical, might it just be cheaper to train an LLM to collate and output news that matches the apparent preferences of various local audiences? Henderson thinks so―and his logic sounds awfully similar to the Y-Lab’s.

By creating presentable local news sources where too few have existed for some time, this LLM newsletter suddenly seems to eliminate a lot of the friction involved in keeping track of local happenings. But, as the article suggests, these LLM newsletter firms―not just Henderson’s―merely displace the labor that paid human local journalists would do, mooch off larger regional and national outlets (where working conditions are deteriorating, too), and can draw from social media―where I’m inclined to analogize people tweeting and posting about local happenings to gig workers who, in this case, aren’t getting paid. Also, these firms steal advertising revenue from existing local papers! The LLM newsletter trend does not reverse the desertification of our media landscape; rather, it dessicates journalists and their publications.

Per Deck, this trend only looks poised to grow:

“Earlier this month, Axios announced a new partnership with OpenAI, which will fund the launch of four new city-specific newsletters in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Kansas City, Missouri; Boulder, Colorado; and Huntsville, Alabama. Far from fully automated, Axios plans to hire journalists in each city to manage these newsletters, who will have access to OpenAI tools.”

As the Y-Lab put it in its introductory poster above, “innovative advances in AI … allow staff to take on higher value, more enriching work.” No doubt this is Axios’s goal for its LLM-wrangler journalist-managers as well.3

The jobs that LLMs are most obviously doing here―those of art scholars and docents, of beat reporters and feature writers―require skill and patience. Yet the ecosystems we have for training and cultivating people pursuing these careers are deteriorating. It’s true enough that LLMs will make all this worse. But more interesting to me as I’m writing this is that the LLMs are displacing rather than replacing their labor. Someone had to write something, now or in the past, for the LLM to have picked it up and interpolated it into the Y-Lab’s “digital docent” or the AI-generated local newsletter.

For the people whose labor is displaced, are they being compensated or valued properly? Of course not―that’s the fundamental problem with AI and art.4 The worst response, I believe, is to suggest fixing this problem by marketizing AI’s use of art through microtransactions or royalty structures. A market in and of itself does not fix the severe power imbalance that AI companies will continue to exercise over the creators of art and writing, nor should the mere existence of a market for a thing morally legitimize the exchange of that thing.

It would also be wrong to stick to the status quo, where AI companies commodify plagiarism itself by stealing others’ works and stripping them of their original context to interpolate them into responses to peoples’ prompts.

So, what’s the right thing to do? I think the answer is, unequivocally, to avoid using LLMs for writing and art whenever and wherever possible.5 But this stance is just not very interesting to me, insofar as the material conditions for quality aesthetic production are deteriorating and these LLMs are being forced into our daily lives, seemingly regardless of what choices we make. It’s all part and parcel of the wider and unabashed algorithm-ification of everything, and all for the profit of oligarchs who certainly don’t have our humanity in mind.6

I can’t claim to have the power to make anyone care about this, but―this is Substack, I’m writing as much for myself as for anyone else―here’s my attempt.78 This debate around LLMs has never been just about broader labor rights struggles and the “material conditions” we live in―it’s also very plainly about ethics: our choices matter because they’re our choices. Who do I want to be?

I think that this “optimized” mode of engaging with art and writing is a subpar, even vacuous, aesthetic experience. Why? Because, when I’m wrestling with interpreting something, whether it’s a painting or an essay or a piece of music or even the news, I like thinking things through myself. I won’t claim I’m always good at it, and crutches―whether in the form of museum audio guides or smart friends or big books or random internet fora―don’t invalidate the work I want to put in. But querying an LLM would make me feel like the object of some opaque entity’s user-experience optimization plans while blunting my efforts to interpret and contextualize things to the best of my abilities. My crutches are part of that context, too. It’s suspect how LLMs displace both of those things; they hide how learning happens.

Through everything and everyone we learn from and engage with, we become vessels for very particular ways of interpreting and communicating knowledge. We might not always be able to immediately identify what or whom we’re drawing from when we interpret a work of art or writing―but the process of learning requires tracing these chains of intellectual transmission, synthesizing our own insights from them, and internalizing them in the process. As more and more people rely on LLMs to summarize, interpret, and contextualize the world around them, the products of those queries and prompts will start to break down those chains. Indeed, by offering people the capacity to more easily and quickly synthesize information, LLMs end up atrophying our capabilities to properly and compellingly synthesize information ourselves. In other words, they undercut the very value they promise to provide.

I should say―I found the Y-Lab by accident. I was puzzling out how to reach the exhibition I wanted to see, the escalator layout confused me, and so I ended up in the basement, where the Y-Lab was the only room open. In hindsight, this itself was hardly a frictionless experience; and, without these unexpected discoveries,9 I wouldn’t have written this essay. So I will continue to appreciate the effort of chewing on things that pique my attention, knowing what I don’t know, knowing whom I’m learning from, and synthesizing it. The only way I can prove to myself that I’m taking my work seriously is to avoid cutting occluded corners in the process.

This is a strong claim, but I stand by it. I’ve been there!

Besides, what does this even mean? Do visitors enter art museums with preconceived preferences about what they’re looking to experience or engage with? To assume visitors know what they want from their stroll through an art museum before a piece of art arrests them is to put the cart before the horse—to the best of my knowledge, that’s not how most people experience art museums! It’s worth asking: “who wants this?”

This reminds me of that old article about how “Axios style” is not fun to read. Would these LLM-journalists make it worse?

If you haven’t read about what’s happening at Spotify, you should. It sounds like the same thing: to get out of paying royalties to record labels and artists, and in realizing that most people listen to music for the background noise, Spotify is slowly flooding its playlists with “ghost artists” and, now, AI-generated content.

This thought is underbaked for now but: I actually believe there’s a difference between blatantly formulaic writing that’s designed for an explicit, almost literally “turnkey” social purpose (like a college essay or a cover letter or a grant application) and, well, real writing. It has a bit to do with Lauren Tuckley’s work on “occluded genres.”

Society, vaguely and writ large, shapes our preferences in advance of our actual recognition of them. The objectification and commodification of our apparent preferences is simply not something we have meaningful control over.

This is me channeling my BD McClay: “And the easiest way (in my experience) to convince people to try being interested in things is just to proceed with the confidence that those things are interesting and that other people will see what you see if you keep looking at it (and then they might even see it and argue with you, which is nice).”