Information processing

Is information a commodity?

One question I’ve received with increasing frequency over the past three months is one I feel mostly unqualified to answer: “What’s the future of artificial intelligence as a technology?” While I have my own opinions about what the directionally correct answers are, of course, I’m just the finance guy, here to communicate whether this technology (however you describe it) even makes money—not what new barrel our society is staring down.

But I do have thoughts about everyone else’s answers. The precedent I see most people leaning on when they try to discuss the future of AI is that of the computer. Financial analysts compare the AI boom to the dotcom bubble no doubt in part because technologists and historians often treat large language models as the next revolution in society’s information technology infrastructure—akin to some combination of the impact of the personal computer, the internet, and the Excel spreadsheet before it.1

Is this comparison instructive or useful? I’m of two minds about it. You can argue that the internet, for example, is very different from Microsoft Excel. But you can also say that they both still represent new ways of processing and disseminating complex information which, to some degree, created their own infrastructures for iterative improvement through their users. So I won’t yet dismiss the comparison out of hand.

One often-referenced piece of information in this debate is the understanding, now widely accepted, that the internet did not radically change the trajectory of productivity growth after its mass adoption. As Robert Solow once put it, “We see the computers everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” And Paul Krugman famously wrote in 1998 that “the internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.” Applying quips like these to AI feels somewhat trite, because the same outcome is almost certainly possible. What’s more interesting to me is the fact that this question isn’t new whatsoever. We keep asking! The productivity paradox is a perennially puzzling part of technological transitions in our information processing systems.

The economist Paul A. David, based at Stanford, wrote a paper called “The Computer and the Dynamo” in 1990 about this persistence, aiming to qualify his peers’ disappointment in the lackluster impact of the “computer revolution” and the “newly dawned” Information Age on productivity statistics with a historical comparison of the computer to the electric dynamo. Riffing off of Solow, David jokes that, “In 1900, contemporary observers well might have remarked that the electric dynamos were to be seen ‘everywhere but in the productivity statistics!’”

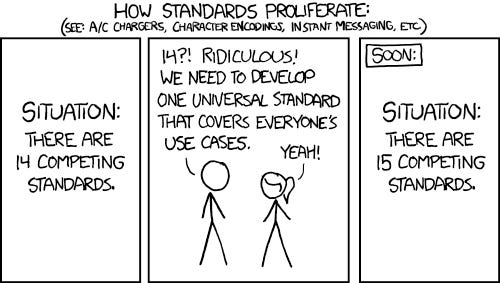

This paper is pithy. David acknowledges the immense technical differences between dynamos and computers—for example, you can’t redesign information processing like you could a factory—but his comparison succeeds because he abstracts away their technological differences to hone in on their similarities as “general purpose engines.” “Both occupy key positions in a web of strongly complementary technical relationships that give rise to ‘network externality effects’ of various kinds, and so make issues of compatibility standardization important for business strategy and public policy.” The adoption of the dynamo, despite its acclaim, was a delayed, protracted affair: The quickest adopters were the most nascent industries that did not have an existing capital stock to depreciate and, in the absence of a class of “middle managers” trained to translate the dynamo’s productivity promises into reality, the efficient integration of the dynamo into industrial processes was a matter of trial and fundamentally tied to demand for the sectors integrating it. There were also, of course, lags and biases in production statistics that occluded new goods produced with the aid of the dynamo from national income accounts.

David’s paper was released in 1990, when the World Wide Web was only a year old. He could not have known how we experience computers and the internet today. But his comparison still feels prescient thanks to his focus on the economic qualities and “network externality effects” of technology, not the technologies themselves.

It’s easy enough to read this paper and compare it to today’s anxieties about artificial intelligence, blow for blow.2 What makes me keep returning to this paper is something else. David qualifies his paper by stating that “information as an economic commodity is not like electric current.” This proposition begs the question: Is information an economic commodity?

David’s paper does not say. But he does provide a set of standards with which to judge the qualities of “information” itself. This paragraph is worth quoting at length for its economistic precision (emphasis mine):

[Information] has special attributes (lack of superadditivity and negligible marginal costs of transfer) that make direct measurement of its production and allocation very difficult and reliance upon conventional market processes very problematic. Information is different, too, in that it can give rise to ‘overload,’ a special form of congestion effect arising from inhibitions on the exercise of the option of free disposal usually presumed to characterize standard economic commodities. Negligible costs of distribution are one cause of "overload"; information transmitters are encouraged to be indiscriminate in broadcasting their output. At the user end, free disposal may be an unjustified assumption in the economic analysis of information systems, because our cultural inheritance assigns high value to (previously scarce) information, predisposing us to try screening whatever becomes available. Yet, screening is costly; while it can contribute to a risk-averse information recipient's personal welfare, the growing duplicative allocation of human resources to coping with information overload may displace activities producing commodities that are better recorded by the national income accounts.

This is an impressively succinct attempt to define the economic qualities of information in comparison to other kinds of commodities. Insofar as I think it’s pretty illegible to non-economists upon first read, however, it’s worth going through this paragraph sentence by sentence to see how its claims hold up.

First, David argues that information lacks superadditivity, or the quality where a whole is greater than the sum of its parts, because it is uncertain whether having more information is necessarily more valuable (however one measures value); and that information has negligible marginal costs of transfer. Units of information are easy to share but hard to value.

He then argues that there’s such a thing as information overload because one cannot easily freely dispose of information. Selling information does not mean losing possession of it.3 Once something is learned, it is difficult to unlearn, and people are generally taught to treat all information as potentially important. David calls this inability to get rid of information a “congestion effect,” akin to a road deteriorating under the pressure of too much traffic. Even if you have more information, it doesn’t necessarily make you are smarter.4

David warns that the easy distribution of information could cause overload because “information transmitters are encouraged to be indiscriminate in broadcasting their output.” The “cultural inheritance” of valuing knowledge predisposes us to screen all information we receive for its usefulness—but screening is awfully time-consuming, potentially preventing us from being maximally productive. Ever the economist, David ends up with an argument about opportunity cost: The more time you spend coping with useless information, the less time you are spending doing something productive—the implication being that technologies that promise to radically simplify the processing and dissemination of information might not actually speed along economic growth in the near-term.

At first blush, I’m struck by how correct I think David’s list is. Each attribute is quite easy to apply to, for example, the challenges of misinformation on the internet, well before LLMs came on the scene. Because screening is costly, and because everyone comes to the internet with a different mental framework for what information might be “superadditive” to their worldview or workplace, the incentive exists to mass-produce what passes for information to see what sticks—brainrot, slop, and falsehoods included. Tech companies very obviously welcome this, creating a world where internet users embrace a post-truth kind of cynicism about information itself.5 David’s argument explains why novel information technologies might even have a negative economic benefit.

But that still does not mean that information is a commodity per se. What I would normally treat as a commodity or as something that can be commodified is—working off of Marx—something that can be appropriated and reappropriated for its exchange value. The problem with information is that you do not lose it in the process of giving it away or selling it. You very literally cannot take back something you say. You can only “dispose” of information by forcing it to be forgotten. How do you wipe consciousness? At this point we’re getting dangerously close to needing a comprehensive understanding of cognition—which any science fiction worth its salt will stress we simply cannot reach.6

One way out of this cul-de-sac is to suggest that information might be a “fictitious commodity,” a la Polanyi. In this view, information is something built into social relationships, like land and labor, and capitalism will seek to commodify information by disembedding it from its fundamentally social, relational, cultural contexts. In this view, people will begin to resist the disembedding of information. This resistance, this elastic response, is what makes a commodity “fictitious.” True enough, capitalism does often use its control over media to decontextualize information—something which people have always resisted. But if information defies the conventional logic of appropriation, I’m not sure it gets to count even as a fictitious commodity.

So, we’re stuck conceding that information is not a commodity at all and cannot be commodified. David, perhaps unintentionally, seems to treat information, as processed by the computer, as a kind of meta-commodity that’s essential for the production of other goods. The computer, in his view, is just better at processing information than its predecessors; it is the machine tool that enables the more efficient production of information. But I’ve read too much science fiction—and just enough snatches of media theory and cybernetics theory—to feel persuaded by this. Information does not exist independent of the institutions and technologies that create it. There is no such thing as a “unit” of information that can ever assert a decontextualized, deracinated existence; content cannot truly be separated from form. And computers certainly haven’t made knowledge production necessarily more efficient: Our thinking isn’t faster. Instead, in the process of building new knowledge structures like the spreadsheet, we—tech companies in particular—have instead discovered that there’s more data to create, extract, and sift “information” out of than ever before.7

This counterargument has a long pedigree. Marshall McLuhan’s insistence that the medium is the message; Dan Davies’ management cybernetics; Henry Farrell’s juxtapositions of markets, bureaucracies, democracies, and large language models as systems for complex information-processing; and Kevin Baker’s work on the social organization of science are all great examples of institutional sociology that defy David’s attempt to drive an analytical separation between information and the capital assets that mediate its dissemination. David’s own admission that our need to screen all information we receive arises from our “cultural inheritance” of treating new information as important reveals that there’s something going on here beyond rational choice. The institutional sociologist Mary Douglas puts it best: “the initial error is to deny the social origins of individual thought.”

If acting on information never precludes anyone else acting on it, and if the stuff we consider “information” always has its significance and meanings pre-massaged, in a sense, by whatever bureaucracies, friend groups, or moral institutions we outsource our understanding of our own choices to in order to organize what’s important—if, in other words, nobody processes information individually—then I think it’s safe to say that information is not a commodity like electricity. It’s something much weirder.

Sam Altman gloated last year that “the cost of intelligence should eventually converge to near the cost of electricity.” Like David, he presupposes that something like intelligence or information is something that can be produced like electricity. Despite speaking from opposite ends of the internet—David at its birth, Altman at its interment—they make an identical category error.

It’s funny: The designs of large language models, as best as I can understand them, betray a more truthful understanding of the nature of information that their designers deny. In mapping out the relationships between units of language through processes that amount to hyper-dimensional matrix multiplication—in building tokens to represent linguistic units and in receiving parameters for relating those tokens via what we call model weights—LLMs all but admit that information is built on the relationships between language structures and that the meanings of their outputs is socially constructed.

LLMs achieve uncanny approximations of written and spoken communication—two specific, if currently popular, methods for how humans might convey information to one another. It’s admirably utopian, really, to try and get as close as possible to those methods. But LLM outputs do not necessarily have any relationship to the interpersonal and social processes for conveying information. Their designers’ sleight of hand is to convince us that their approximations always represent information, anyway, and that this information, when aggregated, represents actionable intelligence.

This lie makes me dislike LLM boosters more, in a way. The hundreds of “AI for X” startups, the idea that you could develop an LLM for any application, suggest that their creators believe that complex information processing technologies will necessarily augment to the output of every existing industry as if the technology aggregated information in a “superadditive” way: where more information means, crudely, “line go up.” But many LLM designers are hamstrung by a shockingly limited imagination of how information can be organized in the first place. Their LLM-powered information processing machines don’t necessarily help anyone find or organize information in the precise way that suits them.

This could very well be the existential condition of information processing: No information system, as advanced as it may seem, will completely bridge the fundamental, last-mile incommensurability between how information is disseminated and how it is received. Into this gap shuffles the task of meaning-making—the one thing that nobody can ever be entirely sure anyone else is doing correctly.

Claude is, by my lights and certainly in the estimation of many of my coworkers and peers, now shockingly competent at processing unstructured data so that it fits pre-arranged formats and finely tuned prompts. But it remains users’ responsibility for figuring out what to do with all that information (if you can even call it information). It’s a game of whack-a-mole: Someone else can always find your outputs too “unstructured” to fit their preferred social and technical systems for processing information. LLMs cannot on their own impose social legibility to their own method of processing information.8

Back to the productivity paradox: Contra David, productivity simply might never be something you can optimize through the deployment of better information technology. New technologies may not, at any point, surmount the cognitive challenges of identifying valuable information, imbuing it with meaning, or acting on it. So it is with LLMs: They are neither necessarily superior or inferior as cognitive aids than the spreadsheets, search engines, and coding languages they’re ostensibly replacing. But their deployment will certainly change the structure of the social and technical institutions that we rely on to perform the cognitive tasks associated with meaning-making.

Many employers, particularly in tech and media, see the deployment of LLM-based products as an excuse to shed workers and, in doing so, turn a profit and please shareholders—and those who don’t might be pressured into this course of action, anyway. The fact that producing slop appears to yield high margins is why the adoption of so-called “generative AI” poses a huge challenge to all manner of service, media, and technology workers. At their worst, tech bros see generative AI as a wholesale replacement for human intelligence and meaning-making.9 They think that information can be appropriated and cognition can be sold. Technically, they are wrong. But their misunderstanding—willful or otherwise, but misanthropic either way—threatens to impoverish us all.

Or even Wikipedia!

I leave this comparison as an exercise for the reader.

This statement is distinct from arguing that information has the qualities of a “nonrivalrous” good. A good is nonrivalrous when two people can use it simultaneously without infringing on how much of it there is. Information might therefore be nonrivalrous, but this argument says nothing about the process of producing and selling information.

There’s no way you’re not thinking of someone you know right now.

We’re already here.

Even if we understood how the brain works, would we understand how our consciousness creates meaning? Maybe—but not in a generalized way. Thanks to cw for this phrasing, and for being my cognition aid through the making of this piece.

I am reminded of the persistence of data-structuring employment through, in the 2010s, marketplaces like Mechanical Turk and, in the current era of “AI-powered” grocery checkout lines and self-driving cars, the displacement of the service sector to computer rooms in the Global South. (Sometimes, “AI” just stands for “an Indian.”)

Tech bros is gender neutral here.